Why Retail Supply Chain Transformations Fail - and how to get it right

Retailers committed to transforming their supply chains need to step back and look at their business model through a different lens.

Thumb through the pages of any business—or supply chain—journal and you won’t look long before you stumble across the word “transformation.” Business professionals across the world are in love with the word as well as the idea of transforming their organizations to tackle the challenges confronting their businesses and put a cloud of dust between them and their competitors. It’s part of the daily business spiel, tossed around in the boardroom and C-suite; in consultants’ presentations; at management conferences; and in the pages of Supply Chain Management Review. But if we ask those same executives just what the word transformation means to them, there would likely be little if any consensus on its definition or how it applies to their organizations or supply chains.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll use the definition that comes up in most searches, which is that “transformation is the process of driving fundamental and sustainable change.” Those two key words are crucial.

Businesses around the world are experiencing never-ending transformations caused by a number of trends at play, including but not limited to the following:

- customer demands for customization and quality at the lowest cost, shifts to services, all leading to ever-evolving business models like omni-channel;

- life-cycle compression, which isn’t limited to just the ever-shortening life-cycle of products (an article last year in Forbes noted that as recently as 50 years ago, the life expectancy of a firm in the Fortune 500 was around 75 years; now it is compressed to less than 15 years and declining even further;)

- intense, global competition driven by players like Amazon, Uber and Alibaba that are changing the rules of the game through their ever-evolving business models,

- disruptive forces such as the Internet of Things (IoT), 3-D Printing, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics Process Automation and even visionary political and business leaders who are creating Smart Cities in places such as Dubai and Singapore.

As if these four were not enough to keep supply chain executives up at night, there are the ubiquitous pressures to grow revenues and contain costs even while keeping up with the moves being made by Amazon, and new regulations in geographies like the Middle East, where former tax-free havens are preparing to introduce value added taxes (VAT) to reduce the region’s dependency on revenues from oil.

Clearly, no organization, regardless of industry, can afford to ignore this tsunami of change. In recent years, however, the impact of these crashing waves has been especially damaging to retail. In part, that is because retailers lived for too long in a state of denial about the changes being wrought on their business models by the Internet; and in part it is because once retailers saw the light, there were no clear and easy solutions. The failure to get things right has created distress for many leading retailers—just look at what has happened to stalwarts like JCPenney, Sears, Macy’s and even Walmart. It will come as no surprise then that retail supply chains are seeing ever-increasing pressures to deliver more from less, be it in procurement or last-mile delivery. They are ripe for transformation, no matter how we define it.

That brings us to another dilemma: While the need for a fix now is imminent, transformations are notoriously slow, and as many as 70% of them fail, according to an article published by McKinsey. There are many theories as to why this is so, but there has been very little, if any, new thinking to over-ride the traditional approach to such programs. It is in that context, based on my experience of working with many retailers, that I offer the following point of view: The fundamental problem in the retail world is that the business model follows the organization model and not the other way around.

That is a different lens through which to view retail transformation. But it is the reason I believe that the phrase “supply chain transformation in retail” is a misnomer, a point I will buttress later in this article with three case study examples of supply chain transformation initiatives from my consulting work in retail. It’s important for me to note that my observations are drawn from my work over the years, and are not necessarily the views of the consulting firm where I now work. The point is that the primary and meaningful way to make supply chain transformations work is to see them not as functional-specific but as organization-wide. In other words, I am pointing a finger at the retail organization model. The different lens that will be detailed in this article should make you re-think your entire retail operating model.

A new model

Like many industry sectors, retail organizations begin by setting up an organizational model: They structure the pyramid, define roles, job titles and lines of report, and then delegate authority. Only after the organization is in place do they design the relevant business model, dictating how the business will operate and go to market.

This last phase of design is constrained by the structure of the organizational model. As a result, managers end up force-fitting ways of working around the organizational structure. By this time, the damage is done.

Such disconnects happen all too often in today’s retail supply chain. These create the perfect storm for failed supply chain transformations, and in retail, they fail often. However, because organizational models reflect the power equations, hardly anyone is willing to acknowledge or bring out the elephant in the room.

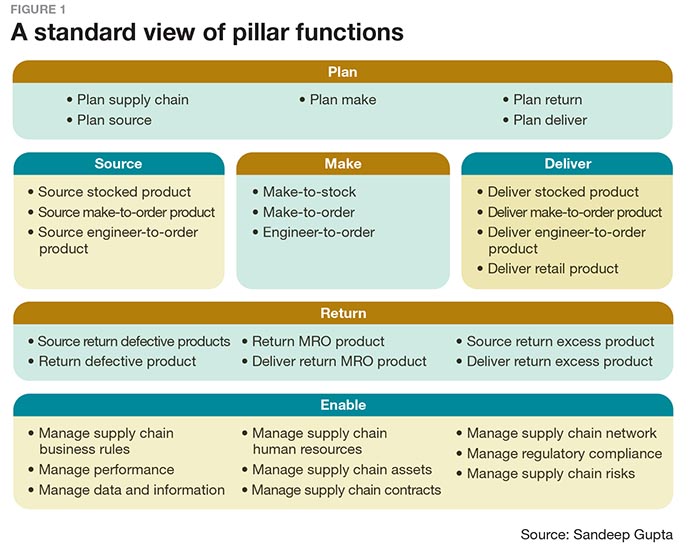

Before we study the real-life examples that will illustrate that point, let’s consider organizations from a large segment of industries that aligned their supply chain functions to the SCOR methodology (Supply Chain Operations Reference Model). Figure 1 is a standard view of the pillar functions one can find in the broader supply chain function.

Most readers will connect with the following typical sub units in their supply chain organization:

- demand/supply planning;

- sourcing and procurement;

- manufacturing (contract and own); and

- operations or distribution and warehousing, logistics and transportation.

Retail organizations, however, typically structure themselves differently: Not only are the terminologies different, but the functional incumbents also see themselves as different. This manner of structuring the business model is the root cause that drives disconnects and creates grounds for the failure of supply chain transformations in retail.

For the sake of comparison, let’s look at consumer packaged goods (CPG) or fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) firms. In those industries, the focus is on creating and fulfilling demand. Demand creation sits with marketing and sales, while the supply chain is tasked with ensuring that the demand is satisfied in the most optimal manner. Hence, these two sets of actions or functions are primary; all other functions play a support role, like a backstage crew.

A retailer’s perspective is different, even though the science is exactly the same as that of CPG/FMCG. Take luxury retail, be it retailing leather jackets, red-soled stilettoes or diamond-studded jewelry.

In this segment, the key decision-making functions are:

- merchandisers and buyers who travel across the globe, read the trends and decide what products/assortments to bring into the stores; and

- planners who hold the purse strings through the OTB (Open to Buy) and work hand in glove with the buyers.

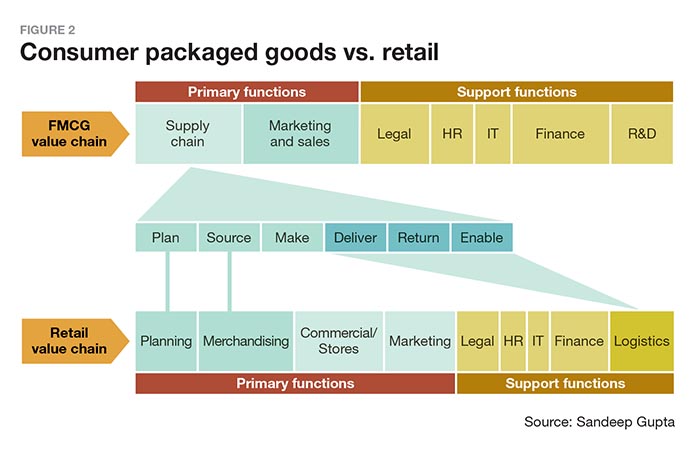

Figure 2 matches the two value chains—that of a Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) or Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) organization with Retail.

As the illustration shows, the retail industry’s value chain breaks apart the traditional SCOR-based supply chain function. Select parts of the supply chain disassociate from the SCOR model and see themselves as radically different; even though the essence of what they do is unchanged.

- The planning sub-unit of a CPG supply chain becomes planning in retail.

- The sourcing sub-unit of a CPG supply chain becomes retail’s buying/merchandising arm.

- “Make” is mostly sub-contractors if the retailer has a private label in the portfolio; otherwise this sub-unit doesn’t exist in retail.

These sub-units do not see themselves as having any connection with the supply chain. In their view, supply chain is only about moving boxes, managing labor/warehouse or driving trucks and delivering stocks to stores and customers.

This structural difference has far-reaching consequences. For example, in retail, merchandisers are responsible for procurement. They are constantly searching, evaluating and selecting new brands and vendors. Additionally, there are various issues in inventory process flow around order split or consolidation (at both levels—order creation as well as execution). This requires ensuring certain capabilities to manage multiple sources of supply in an optimal manner. Think International Commercial Terms (Incoterms).

Question: Why is the logistics function not engaged with contract discussions with vendors to ensure that the most appropriate Incoterms have been included?

The need for retailers to transition toward omni-channel is now a given. Omni-channel leads to stores rationalization as is evident from the number of stores being shuttered by major chains as varied as Target to Walgreens and from Office Depot to Barnes & Noble, with news of new closings trickling in every month.

Question: The closure of stores has a direct impact on the design of the supply chain network. Why, then, isn’t supply chain engaged during the decisions to open or close stores because they have an impact on the efficiency of the supply network as well as the total landed cost of the merchandise being sold?

The real world

Let’s now review the details from some real-world retail examples from my consulting work. The first is a retailer that operates in multiple segments and has a large footprint of brick-and-mortar stores in emerging economies.

During periodic reviews of the financial performance for one specific line of business, the CFO repeatedly noted that inventory levels were trending upward. The impact on the availability of working capital was pinching the business. To address the issue, the retailer brought in a team of consultants to look for ways to reduce inventory levels.

The consultants undertook a detailed review, studying the product flow, actual lead times, ordering mechanisms, aging of SKUs at the store level and other dimensions. They drew up a road map for transformation that was embedded with a set of operational and strategic solutions. They claimed that the proposed solutions could reduce enterprise inventory levels by as much as 50% without any adverse impact on customer experience.

Skeptical of the claim, the divisional vice president dismissed the recommendations, claiming that based on his years of experience, a 50% reduction in inventory was pie in the sky. He was extremely wary of moving forward on this transformation. Still, the CFO asked the consultants to implement a pilot of their recommendations. The consultants drew out a phased approach that clustered brands into waves based on certain criteria and then implemented the plan in select solutions. The first wave focused on 10 high-volume brands sourced from a common market.

A few months later, the consultants reported that the pilot had reduced the inventory of those selected brands by 6%. After the finance team vetted the realized benefits, the consultants were sent on their way with a pat on the back while business leadership decided to proceed with the rest of the implementation on its own. After two years, the business failed to capture more than that initial 6% reduction in inventory.

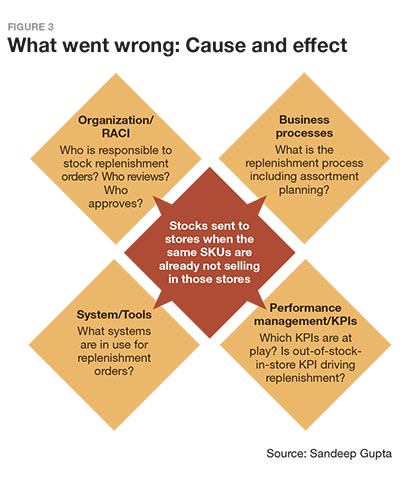

The essence of what went wrong (and therefore, the various recommended solutions) was across all dimensions of the operating model. Figure 3 is an example of how various issues had created an inter-play of cause and effect.

The center of the illustration shows one of the hypothesis used by the consultants: New inventory stock was being sent to the stores even though the stock already on the shelves was not selling, compounding the inventory issue. In fact, the hypothesis had proven true. The schema provides a glimpse to the types of questions that were raised during the deep-dive on each dimension of the operating model—Organization (or People), Business Processes (including Policies), Systems and Performance Management.

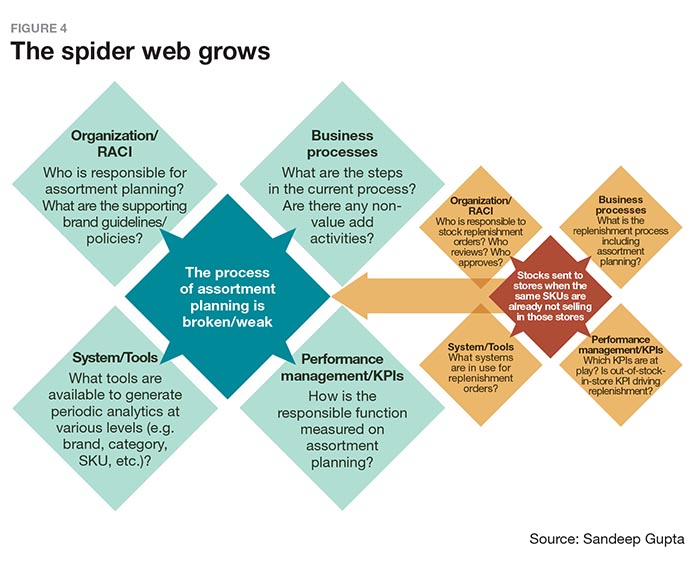

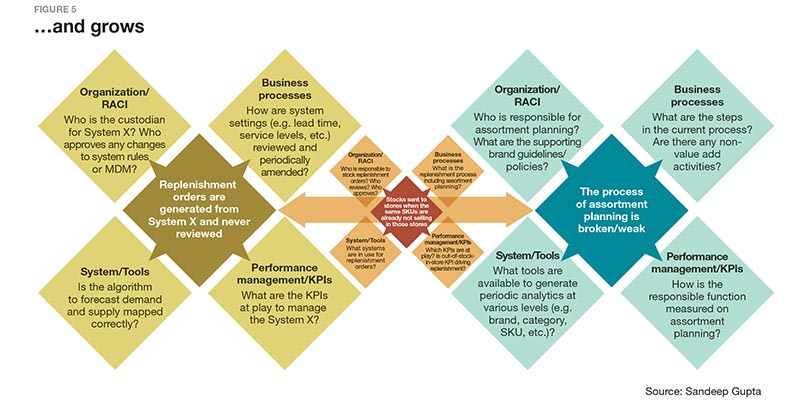

Think of the “5 Whys” from Lean; the true hypothesis was like a symptom and the questions across all dimensions were searching for the root causes and testing for direct correlations. As the consultants delved deeper, the chain of root causes and their linkages grew and grew like a spider web. Some questions, in turn, became hypothesis that needed further validation. The causal relationship across multiple attributes was deep-rooted and spread out across all dimensions of the organization. Slowly the canvas, as illustrated in Figure 4, became larger.

Imagine the true scale of the transformation needed to address the business issue. This was a gangrene of sorts, but amputation was not possible.

Real transformational success requires that an organization keeps peeling back the onion layers to finally reach the core and then design relevant solutions. In this instance, growing inventory levels are not like the common cold—you cannot address it with over-the-counter medications.

Real transformational success requires that an organization keeps peeling back the onion layers to finally reach the core and then design relevant solutions. In this instance, growing inventory levels are not like the common cold—you cannot address it with over-the-counter medications.

Even worse, this retail organization did not have either the appetite nor the courage to progress on the implementation and ask the relevant questions. Whose problem is inventory? Will the problem-owner also own the solution? Given that the transformation program cut across planning, buying, technology, HR, etc., who would sponsor the initiative, if not the CEO? Is this really just a supply chain transformation program or is it an organization-wide transformation program?

In this case, the ultimate outcome is easily predictable: The constant bleeding or hemorrhage will one day lead to the death of this business unit; they are only postponing the inevitable.

Let’s look at another example: This franchise retailer has been in business for more than 40 years and has built an envious portfolio of global brands. A few years ago, it began to face eroding profitability due to changing market and economic conditions. As various governments opened their markets and reduced Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) restrictions, some high profile brands ended their marriage with the franchise partner and went independently to market. Additionally, the disappearing wage arbitrage across markets led to a rise in labor and operating costs.

In short, revenues as well as profits came under severe pressure. As a result, the CEO and CFO concluded that unprecedented times needed creative thinking and were keen to initiate a series of projects. Even support functions, such as logistics, were required to identify topics or themes of transformation to achieve a step-change in profitability.

In fact, logistics was tasked with optimizing total landed costs (TLC) as an avenue of potential savings. However, because TLC includes the cost of the products, which sat with the buying function, the scope of logistics’ study was restricted to other cost elements, excluding product cost.

The study required some very heavy data lifting to understand the historical flows of ordering cycles, receipts, the time that inventory sat idle in a warehouse before it was issued to a store, including all possible variations of cross-docking and direct store deliveries. The franchise nature of the business did not permit a like-to-like comparison to international benchmarks on TLC. However, the project team was able to develop some very specific proposals that could shave 7% to 12% off their baseline cost. The challenge was that most of the proposed solutions were strategic in nature.

One solution called for a re-examination of the Incoterms negotiated with the brands. The study highlighted a number of instances where the retailer was operating on unfavorable Incoterms. For example, some brands operated on delivered duty paid, or DDP, but the retailer could save significantly on shipping costs if the Incoterm was changed to ex-works (EXW). Analysis showed that there were other potential savings involving different choices of Incoterms.

The challenge to realizing those savings was that the higher logistics costs had their roots in the way buyers were negotiating vendor contracts. So, what began as a logistics transformation initiative made little progress because the route to success passed through buying, planning and merchandising. The question for the retailer was: Where should real transformation begin? As is mostly the case in retail, the responsibility for TLC had been handed to the supply chain (logistics), even though the buyers select the brands and negotiate prices and volumes using the OTB worked out by planning. In the case of this retailer, most buyers had no idea where the merchandise would be sourced from, how it would be shipped or which Incoterm was most suited to their organization. Some buyers did not even know the existence of the word Incoterm, which is the key to managing TLC.

It will come as no surprise that the transformation died before it was born.

I present one final real-life example. The logistics function of an apparel retailer operated as a separate service provider, with a charge-back model based on the unit volume of products being handled. Every year, in the budgeting rounds, logistics came under pressure from the internal clients/P&L owners to push this unit cost down.

A diagnostic review highlighted that the warehouse staff was often busy with fire-fighting activities that added no value. A more detailed study concluded that the bulk of these activities were related to inbound shipments. The key issue was that when shipments from non-EDI brands arrived at the warehouse, the corresponding purchase orders were often missing in the ERP system.

As a result, even though the warehouse had physical custody of the merchandise, it could not take ownership on the books, leaving the stocks uninsured and in quarantine on the docks. What’s more, back-of-the-envelope calculations concluded that logistics was spending as much as 25% to 30% of its efforts on such non-value added activities.

But while logistics was bearing the brunt of the case of the missing purchase orders, it had no role in procurement, which was done months earlier, or in the posting of purchase orders. That raised at least two questions: How can logistics deliver operational and unit cost reductions when activities beyond its scope affect its overhead? More importantly, how do you convince internal customers that they are the real culprits here?

Ultimately, planners and buyers viewed the creation of purchase orders as a mundane, non-glamorous job that could be procrastinated. Of course, the “do it later” mentality too often meant that POs were never issued until the fire fighting was underway. Logistics would have to take the stocks into the warehouse to avoid paying demurrage, keep a manual count for all such shipments and follow up by the hour. In parallel, all kinds of multiple manual handling kept happening until the final put away or cross-dock was completed.

The true impact of this could be devastating for those retailers that have implemented an omni-channel strategy, where demand fulfillment is completely dependent on how quickly can you move your products from receiving to shipping. No one can deny that the supply chain is the backbone of omni-channel fulfillment: You either perform or perish.

Transformation success

In all three real-life examples, the reference to buying and planning functions is neither deliberate nor accidental. There is no denying that these functions are lynchpins in the success or failure of any retailer.

What’s more, if you look at transformation through a new lens, it is clear that their genesis is in the supply chain. Until retailers recognize this, most supply chain transformations will continue to fail or deliver very little in the way of tangible business benefits.

Based on my consulting experience, retailers need to go back to the basics and bring in the three very important considerations below.

- Retail is all about the supply chain: Your organizational model should reflect this.

- Only those retailers that have supply chain talent and thinking embedded across the various functions will be successful in the future; that includes buyers.

- Any supply chain transformation must begin as an organizational transformation in scale and depth—know it, and deal with it.

Based on the examples I have shared, I believe that when the organization model precedes the business model, the organization has a written end-date for itself. This single, fundamental flaw becomes the bane for many transformations. Instead, if retailers first paint the canvas with “how do we want things to be done” and then go on to define “who will do what,” they may see a completely different horizon—one full of transformation success and positive results.

Sandeep Gupta leads the Business Excellence team at Al Tayer Group, UAE. He can be reached at [email protected].