Want to Innovate your Supply Chain? Break the Rules

By clearly understanding the nature of the rules and the details of your supply chain, you can better determine where and when rule-breaking makes sense.

From college courses to on-the-job training to professional seminars, we’re taught that supply chain is a complex set of processes that follows specific rules to achieve the best results.

Yet most supply chain innovations and breakthroughs evolve from situations where the basic rules were actually broken or changed. Is there a disconnect?

Breaking the rules has to do with knowing when it’s beneficial to make an exception to accepted practice or to challenge the conventional answer. It entails scanning the horizon for new technologies, best practices, or approaches that change the paradigm of how we do things.

Winning companies often excel because they saw a situation differently and were willing to take the risk and the initiative to break with the accepted logic. Innovation is all about breaking the rules. If you don’t look outside the box, you will become imprisoned inside it.

The challenge for management is first to create a culture that looks outside the box. Once that’s in place, supply chain executives can identify which rules should be broken or challenged and how; when the timing is right; what specific actions need to be taken; what are the economics and operating levers; and how to harvest the benefits after the rules are broken.

Breaking the conventional supply chain rules is not the right strategy in every instance. But when it does make sense, it can lead to truly breakthrough results.

The real secret to successfully breaking the rules is to know the rules intimately in the first place. When you understand the foundation of a rule, you better understand the logic and the strategy upon which the rule is based. That yields a much clearer sense of which rules restrict rather than support your supply chains.

Below we address five time-honored supply chain “rules” that need to be challenged—not necessarily broken, but at least carefully analyzed to see if a departure from the rule makes sense for your organization. Each segment concludes with a brief recommendation on how to approach the particular rule.

Rule 1: Supply chain is not strategic

Historically, the supply chain has been considered one of the least strategic corporate functions. Its nuts-and-bolts reputation evolved from its transportation and warehousing roots. While much has been said about the supply chain’s strategic value, comparatively little has been done to back up the words.

Certainly, the development of advanced information systems, material handling technology, sophisticated order management and customer intelligence systems has improved supply chain operations dramatically. And procurement, manufacturing, and logistics functions are becoming increasingly more integrated—with some even reporting to a Chief Supply Chain Officer (CSCO).

Yet, our research and experience finds that most companies still view their supply chain mostly as a cost of fulfilling demand.

If we are going to be innovative, we need to challenge the notion that supply chain activities are primarily a tactical cost lever. The reality today is that supply chain is more than fulfillment operations. It has become the most critical link to the strategies and tactics of marketing, customer relationship management, and market and service segmentation.

The most successful companies integrate their business, marketing, and supply chain strategies. In their view, cost is not the central focus of supply chain performance management. The strategic value of supply chain operations is in fullfilling the marketing strategy to delight customers and grow market share—not just fulfilling orders at the lowest cost.

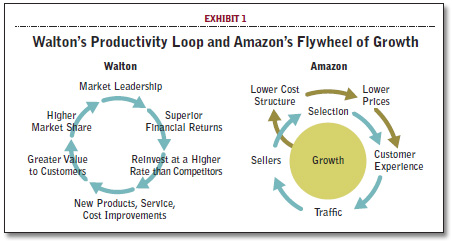

Sam Walton of Walmart and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos both got this. They understood the value of leveraging supply chain capability to delight a critical market segment, or to support an initiative that differentiates them from the competition, or to focus on the “big” economics (top line or total profit, for example) rather than traditional supply chain cost minimization. Bezos is often credited with developing the “Amazon Flywheel of Growth” on a napkin.

The reality is when several senior executives from Walmart joined Amazon, they brought with them the concept of Sam Walton’s “Productivity Loop,” which Bezos then adapted to Amazon. (Exhibit 1 depicts the Flywheel and Productivity Loop.) The point is that for both Walmart and Amazon, value and service drive revenue growth; revenue growth drives efficiency, leading to more value and more customers; more customers drive more efficiency, value and growth; and the loop or flywheel continues to spin.

Consider the growth and leadership of these two companies as well as CVS (among many others) whose ability to deliver their promises consistently and reliably is the backbone of their success. Each of these companies has changed a segment of the retail industry by developing better, deeper, broader supply chain service capabilities and promoting them as differentiators against a broad range of competitors.

Walmart brought availability, selection, simplicity, and low cost to customers who had rarely experienced any of those benefits before. The entire Walmart model was built around consistency and reliability focused on maximizing margin per square foot, product availability, broad assortment, store consistency, and friendliness. To every characteristic, supply chain provided the resources, leverage, and capability to execute.

Amazon, by focusing on delighting its best customers and deeply understanding their needs while scouting for the next “best customers”, has demonstrated that services that delight customers can produce dramatic growth in both the top and bottom line.

The underpinning is the company’s capabilities with regard to warehouse design and management, supply chain software development, and transportation management as well as the processes that interface these areas. Amazon’s amazing business success flows from a strategy to maximize margin per box rather than from any singular focus on absolute supply chain cost reduction.

CVS is in the midst of what could be a sea change in “drugstore” retailing. By recognizing the value of the mail order market as it shifts to serve older adults, CVS has followed through with the strategy of acquiring the requisite fulfillment capabilities and linking them through supply chain strategy to its ongoing business. By understanding the strategic value of alternate distribution channels and linking them, CVS has repositioned itself as the market leader.

Rule Recommendation: The best results come from the strategic integration of supply chain with marketing and sales, with finance, with suppliers, and with customers. Moving from operational integration to strategic integration is tough; it’s fraught with concerns of losing control and sharing sensitive information. Yet the dramatic breakthrough results of the leaders prove that the risk can be worth taking.

Rule 2. All customers are created equal

Most of us have heard this platitude throughout our careers; in fact, we often see it stated as a formal company policy. Consider the extremes, though, with respect to this high-sounding ideal. A company’s most important customer usually earns that designation because it is large, has a big demand for our product, and has a continuing, profitable relationship with us.

At the other extreme is a fair weather customer, one who buys our product sporadically, is hard to deal with, pays slowly, and is only very marginally profitable to us. The practices of the first customer allow us to carry minimum safety stock to cover its demand, and cycle stock to process and handle their demands on a largely routine basis. None of this applies to the second customer. Is this equality?

The truth is that customers are not created equal—but it takes insight to understand what that really means. In a nutshell, “all customers are created equal” often means that the worst customers get better service than the best. In the two opposite examples just described, the second customer, because of its sporadic demand and uncertain requirements, requires extra inventory and order processing and handling time.

At its worst, this customer’s volatile demand can actually steal inventory and responsiveness from the most important customer. In such cases (which are not all that uncommon, by the way), “all customers created equal” really can mean “best service for my worst customers.”

Again, a disconnect between marketing and operations contributes to the problems associated with this rule. For operations, the biggest challenge often is understanding which customers are “best.” Size, by itself, may not be the indicator of importance. Total profit contribution or long-term profit potential would be a better indicator.

Most of us are familiar with Pareto and the 80-20 rule (20 percent of our customers generate 80 percent of the business). Experience suggests that this rule is only the tip of the iceberg. In virtually all industries, a very small percentage of customers (often 5 percent or less) account for an amazing proportion of a company’s profit (40 to 60 percent, or even more). Losing one of those customers can be disastrous, while adding one can make the company’s numbers for the next year.

Market leaders look at the 80 percent of the customers that aren’t producing much profitability and develop a strategy to grow them or lose them. Supply chain leaders also know this secret. This focus on customer profitability is often the driver of the world’s best companies. In any case, finding and understanding which customers are truly most important will enable you to treat them so well that the results will be exceptional.

Think about the heyday of Dell computers, when the company gained spectacular market share by breaking the “all customers are created equal” customer service rule. By building channels, capabilities, and systems that provided different levels and packages of service to each segment—as determined by the segment’s profitability—Dell had the full range of customers singing the company’s praises in harmony, even though the melodies that each segment heard were unique.

And today, as Dell’s customer base and market segments are shifting with changes in the personal computer market, Dell is challenged once again to rethink and reshape its supply chain strategy to meet new customer segments and requirements.

Rule Recommendation: The best results come when supply chain operations fully understand the needs and requirements of different segments and customers. The leaders define their different supply chains to meet and delight the customers in the selected and targeted segments and build their supply chains backward based on serving the customers’ requirements. Supply chain strategy is most effective when aligned with the company’s market strategy.

Rule 3: Manage for minimum cost

Supply chain is an operations-driven function. As supply chain professionals, we are schooled and trained in selecting the steps and executing them perfectly in order to drive costs out of the process. Yet in many situations, forgetting about costs and focusing on profit can produce spectacular results.

The two most successful retailers in the U.S.—Walmart and Amazon, who we introduced earlier—owe their success primarily to integrating their supply chain capabilities with their market strategy. Moreover, both achieved greatness because of their disdain for traditional supply-chain focus on cost efficiencies rather than value contribution.

Walmart grew by having “too much” inventory, while focusing on the prices customers pay rather than the margins generated from the traditional retailer supply chain. Sam Walton saw multiple retailers, each with their own store, selling different product categories.

He believed that by extending the assortment across many categories (the long tail) in a single store, he could offer lower prices while increasing inventory velocity and the margin per square foot. In addition, he could further increase his margin by consolidating volume and leveraging his distribution function. Walton would make the investment if it would generate long term advantage.

Amazon, starting with an emphasis on books, has become the broadest and most dramatic supply chain and fulfillment company the world has ever seen. But importantly, its main focus is not on minimum cost but rather on consumer satisfaction.

Founder and CEO Jeff Bezos has stated publicly that if customers are happy enough, the top line will grow fast enough and the bottom line will follow (even if it is a low percentage).

By focusing on increasing the margin per box, Amazon supply chain management can look at increasing revenue per lane vs. reducing transportation cost per lane. Breaking the rule changes the game.

The leaders understand that corporate success depends on how well the supply chain is orchestrated within the corporation’s vision and overarching strategy. Managers of the truly great supply chains recognize that cost minimization is a “nice to have” within the framework of the “must have” long-term health and success of the corporation.

Supply chain executives have a responsibility to always recognize that supply chain is one of the few corporate areas entrusted to balance objectives rather than simply minimize them.

A major manufacturer of commercial air conditioners had focused on minimizing inventory and number of stocking locations. Over the years, inventory turnover increased substantially, and warehouses were reduced by two-thirds. Nonetheless, market share eroded as customers increasingly viewed the company as being non-responsive and old-fashioned.

Recognizing that a large majority of sales were for replacement systems rather than new construction, management determined that fewer locations meant slower responsiveness to that part of the market that was not price sensitive but truly cared about availability.

Thus, it tripled the number of warehouses and simplified product design for the replacement market, allowing for fewer SKUs to cover market demand. Although field inventory soared under this unconventional approach, the company gained 20 share points and profit doubled.

Rule Recommendation: The principle of minimizing cost is certainly valid, but it must be seen within the context of inventory availability and other supply-chain outcomes that can have a profound effect on the demand, sales, and price levels of your company’s products. By understanding the intersection of marketing and operations and focusing on the customer to design the supply chain backward, that vision becomes clearer.

Rule 4. Always use optimization models to determine the location and level for manufacturing and inventory

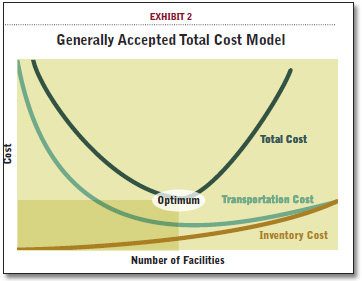

There are several methodologies used to make location decisions and many proven modeling techniques to work through the process. The analytics within most models generally follow the rationale that transportation costs go down with the number of locations, whereas inventory-related costs increase with the number of locations. The optimization process uses forecasts of product demand, inventory carrying costs, and transportation cost as its inputs.

Each cost arrives with its own challenges, however. For product demand, three to five year forecast data by geographic location and stock keeping unit are typically utilized. But such data are historically inaccurate—even on a near-term basis. For inventory carrying costs, computations include a company’s cost of money, which varies with the prime rate and the company’s economic situation, not to mention international exchange rates.

For transportation costs, computations include fuel surcharges and lane volumes, both of which vary substantially from year to year.

Uncertainty or volatility in sourcing, mode, and third party contracts also can have a substantial effect on the model’s outcome.

Given all of these factors, the “optimum” is rarely a clear finding. Most individuals think the graph of total cost looks something like a “V,” with a clear minimum point. (See Exhibit 2.)

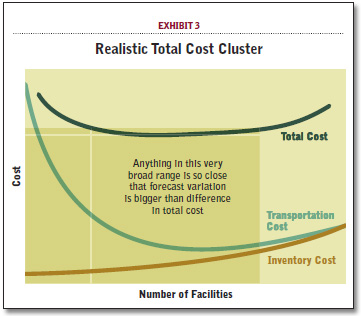

However, almost always the graph is shaped something like an old bathtub with a very long, virtually flat center area. (See Exhibit 3.)

Variation between what may be the minimum and perhaps 10 or 20 alternatives is far smaller than the variations caused by inaccurate forecasting and data volatility.

The following illustrates our point. A regional food manufacturer restructured its entire distribution system based on total acceptance of a highly sophisticated optimization model. Four years later, because of small shifts in customer demand and dramatic increases in transportation costs, its total supply chain costs had increased by 150 percent.

At the same time, a competitor had looked at its new product rollout strategy and determined that they had virtually no idea of expected demand.

The company president decided to “roll the dice,” utilizing stocking distributors, specialized retailers, extra inventory, and several alternative transportation methodologies to cover the unknowns.

Rather than trusting a model using highly uncertain “guesstimates,” he invested in cushions that kept the evolving but uncertain customer segments satisfied. This apparently high-cost solution kept supply-chain costs level while effectively supporting the unpredictable patterns of new product growth.

Rule Recommendation: Use optimization models as rational guideline tools. However, trust only the ranges of the results and their consistency, rather than blindly accepting the answers as absolutes. Further, make sure the assumptions used in the model match the market conditions that you actually face. And, if you do use the models, consider multiple scenarios and use them frequently. All things change.

Rule 5: Ship every parcel order the day the order is received

This misguided maxim evolved from a different era, when at one time the practice made sense. The truth is that parcels move fastest when they become truckloads, and taking steps to consolidate shipments can have a profound effect on the time—to say nothing of the cost—of a shipment. Effective supply chains are built around the total elapsed time of the order cycle, not the time of one event (“ship today”), even if it is an extremely visible activity.

To illustrate, a specialty Internet retailer of products to aid handicapped customers proudly promoted its same-day shipping policy. Yet company management could not understand why a competitor that clearly did not follow the same policy continued to maintain a competitive advantage.

The competitor’s positioning broke the rules: they had no interest in shipping every parcel the day it was ordered. Rather, they accumulated shipments within various geographic areas, combining them in truckloads, which in fact crossed the country far more rapidly than the small shipments. In addition, this approach avoided the higher rates associated with LTL or parcel shipments.

Simply stated, the competitor that appeared less responsive actually made more profit and satisfied customers far more than the retailer. Effective management of consolidation can produce dramatic results—even if it runs counter to traditional thinking.

Also consider Amazon’s Prime Customer incentive: free two-day shipping for an affordable annual fee. Why two day? By guiding its customers to a two-day shipping window, Amazon collects order, inventory availability, and cost information for each customer, distribution location, and shipping method in its network.

Armed with this information, Amazon’s optimization system can determine the best location to ship from at the lowest total cost. Employing a virtual inventory system that considers all inventory as one accessible resource, orders are consolidated, transportation optimized, and the volume concentrated along lanes to maximize line haul while minimizing parcel. As volume grows, margin per box grows with it.

Rule Recommendation: Often, the implications of promises made are unintended and undesirable. By clearly understanding the service effects of alternative actions, it is often possible to deliver more of what the customer wants at a cost that is surprisingly low. It is critical to understand the full impact and flow of decisions: what may appear to be optimum or at least desirable can easily have an opposite effect.

Which Rules to Break?

Which rules should you consider breaking? To answer this question, it’s critical to understand the fundamentals and the assumptions behind the rules. For example, if the rule assumes a normal demand distribution, it may be appropriate to break the rule if demand is not normal. If a rule depends on level volumes, look out for spiky or seasonal volumes.

If a rule is in response to an operating system or a customer or supplier relationship, challenge it if the system, the customer, or the supplier has changed. And if the rule relates to combined characteristics, prepare to challenge its application to individual ones.

It’s also important to understand that rules flow from assumptions that are based on a point in time. Times change, technology changes, everything changes.

Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) algorithms are a great example of ever-changing assumptions that affect the rules. Just as customers are not created equal, neither are suppliers nor inventory items, nor manufacturing processes or cost.

Variability in cost, demand, yield, lead time, capacity and the myriad constraints that comprise the assumptions made to calculate EOQ are always changing. Yet, many, if not most, companies use a single EOQ algorithm to calculate replenishments and their ERP systems don’t recalculate the EOQ quantity on a regular basis.

Disappointingly, many companies have not documented their supply chain processes and practices. In fact, we find that most companies haven’t even defined their supply chains. Yes, that’s plural; companies usually have multiple supply chains. The supply chains differ based on the different product categories they sell and the different customer segments they serve.

Hewlett Packard, for example, has different supply chains for servers, PCs, and printers as well as for different industry, business, and personal customer segments, not to mention geographic supply chains (see the article How HP Visualizes its Supply Chain using Geographic Analytics). As supply chains are defined and processes documented, management can more effectively benchmark performance and best practices.

By knowing the fundamentals and assumptions and by clearly understanding their supply chains, companies can more effectively review the process rules governing process performance, identify assumptions that may have been subject to change, and—most importantly—pinpoint which rules to “break” for improved performance.

If you are looking to produce step-change results, you have to take the steps to understand, identify, evaluate, and innovate the processes. As our case examples illustrate, these results can go beyond financial improvement; they can be game changers that can lead to market advantage.

It is critical to recognize the conditions that suggest that breaking the rules may be in order. These could include, for example, new competitors in your market, changing customer preferences, rapidly changing technologies, service and warrantee difficulties, exceptional weather patterns, or unpredictable seasonality demands. In short, rule-breaking scenarios can come from any direction and take any form.

Most important, in deciding which rules to break you have to look across process boundaries. How are supply chain processes affecting and being affected by sales and marketing processes? Over the years, most of the breakthroughs and innovations we have observed resulted from companies managing the intersection of marketing and operations.

Significant financial gains are made when all of the competitive levers are pressed equally. That’s the lesson learned from Amazon, Walmart, P&G, and other market leaders. When you clearly identify the levers of growth and align their processes for competitive superiority, innovation and breakthrough results can be achieved.

Finally, be very sensitive to trading partners’ technologies, priorities, and modes of business. In some cases matching them can provide immense advantage; in other cases what works best for them may be nothing more than a disruptor to you.

Overall, winners are those organizations that understand the “why?” as well as the “how?” of the rules that supply chain people follow. And, all the while, they look for the thin rays of light that occasionally shine between the thick absolutes of tradition that we are all expected to follow. Quite often, those rays of light are nothing more than their common sense screaming out: “In my gut, I know there’s got to be a smarter way of doing things.”

Article Topics

HP News & Resources

Pacific Rim Report: High-tech must address slavery in their supply chains Update on 3D printing NextGen Supply Chain: Update on 3D printing, Part 2. Operational Analytics Big Data and Analytics Focus in the Travel and Transportation Industry Embrace Convergence HP Converged Infrastructure Delivers for UPS More HPLatest in Supply Chain

Microsoft Unveils New AI Innovations For Warehouses Let’s Spend Five Minutes Talking About ... Malaysia Baltimore Bridge Collapse: Impact on Freight Navigating TIm Cook Says Apple Plans to Increase Investments in Vietnam Amazon Logistics’ Growth Shakes Up Shipping Industry in 2023 Spotlight Startup: Cart.com is Reimagining Logistics Walmart and Swisslog Expand Partnership with New Texas Facility More Supply Chain