The Emergence of the Strategic Leader

The strategic supply chain requires a new kind of leader; one with skills and orientations not currently found in many supply chain managers, this article describes what's needed to complete that change, and the steps to get there.

Supply chain management is on the cusp of a metamorphosis.

For as long as the term has been in use, supply chain practitioners have been tacticians.

They focused on making sure that the production lines rolled and orders were filled in the most cost efficient and timely manner.

Execution and firefighting were highly valued skills.

The profession even had its own language and metrics, apart from those used at the C-level.

Whether those same skills will serve tomorrow’s supply chain manager is very much up in the air. That is especially true as supply chains are transforming from tactical to strategic.

In this new model, the key challenge is to harness the supply chain to deliver on a business’ go-to-market strategy by focusing on a broader set of outcomes - outcomes such as responsiveness, innovation and sustainability.

Indeed, many supply chain managers are questioning whether they or their organizations will have what it takes to make this change.

In a recent survey of supply chain issues published in CIO Journal, Deloitte noted that the major concern facing the executives it surveyed was the lack of adequate supply chain talent.

Indeed, only 38% of the respondents were confident that their organizations had the required competencies today. They were even less optimistic about the future: Only 44% felt confident that they would have the skills required to meet their needs five years from now.

On one hand, this finding emphasizes the fact that there is a supply chain talent crisis - a fact of which most supply chain managers are only too painfully aware. Yet, of more importance than the numbers is the nature of the skills respondents believe will be required of supply chain leaders in the future.

As can be expected, being technologically savvy is seen as important (including the ability to understand and integrate the technological capabilities offered by such developments as Big Data analytics, 3D printing, artificial intelligence and wearable technology); but the management skill that causes the greatest amount of concern is that of critical thinking and problem solving (Figure 1).

This finding leads to three critical conclusions:

1. The supply chain is changing; metamorphosing from a tactical entity that is often seen as more risk than benefit - a necessary evil where the “best” supply chain is the one that you never hear of - to being seen as a strategic capability that enables and enhances the ability of a firm to gain a significant competitive advantage in the marketplace.

2. The existing supply chain manager is not up to the task of managing or tapping into the promise of this new supply chain.

3. A new type of leader is needed to manage this new supply chain.

While that may sound simplistic, there is other evidence to support these observations. Currently, the department of supply chain management at Michigan State University, in conjunction with APICS, has undertaken “Supply Chain Management: Beyond the Horizon,” a multi-year study focused on identifying the developments that will affect the supply chain of the future.

The findings to date support these three conclusions. This crisis exists in part because of the inability of the current generation of supply chain managers to clearly articulate that supply chain management is not a solution (like Lean or Total Quality Management) but rather a set of capabilities that can determine what the firm can and cannot do.

In a recent article in Forbes, SCM World’s Kevin O’Marah contended that the supply chain should be aligned with the desired outcomes prized by the key customers and the strategic promises made by the firm, as contained within the value proposition.

We could not agree more that in tomorrow’s supply chain, strategy will be as important - if not more important - than tactics and execution. And tomorrow’s manager will need to understand how to speak the same business language as senior management.

Read Kevin O’Marah's Future of Work: Four Supply Chain Careers for 2025

In this article, we intend to expand on the three major conclusions previously presented. We will examine how the supply chain is changing (and the factors that are causing this change). We will look at why the current crop of supply chain managers will have difficulty meeting the challenges and demands created by this new supply chain.

Finally, we will explore the skills and capabilities demanded of the new supply chain manager; requirements that transform the supply chain manager of today into the supply chain leader of tomorrow.

As part of this final discussion, we will discuss the challenges facing firms, educational institutions and professional societies as they struggle to develop this new generation of strategic leaders. However, before we discuss the challenge of creating the leaders of tomorrow, we must begin by understanding the changes now taking place in the supply chain.

The New Supply Chain

Since the term was first introduced in the Financial Times in 1982, the supply chain and how it is perceived within the firm has greatly changed. Initially, managers outside of the supply chain saw it as tactical, consisting of terms such as planning horizons, capacity, advanced delivery notices and Lean.

At the heart of supply chain was a combination of boxes, trucks, factories and shipping orders. CEOs and senior managers only became aware of their supply chains when there was a disruption, especially one that made the news.

They learned the hard way that supply chain disruptions can hurt their firm operationally and strategically. Thanks in a large part to academic research, they also learned that a supply chain disruption was often followed by a 40% drop in their stock price that took nearly two years to recover.

This led to an interesting phenomenon - the attractiveness of the “invisible” supply chain: Because the only time senior management ever heard about a supply chain is when something went wrong, the “best” supply chain must be one that they never heard about.

That view is changing - and changing radically. Managers and corporate leaders are starting to recognize the strategic value of their supply chain to their firms. This change can be attributed to the following factors:

- Increasing rate of technological advances that are rooted in the supply chain. The media is awash with articles about the Internet of Things (IoT), 3D printing, Big Data and analytics and autonomous vehicles (self-driving trucks and cars). These new technologies are changing how firms design, build and deliver products, and how they interact with their customers. Tire manufacturer Pirelli has introduced sensors into truck tires that collect information about the durability and performance of its products. That is allowing Pirelli to offer its customers new capabilities for better vehicle protection and control and should lead to better tire designs in the future. Similarly, Amazon is experimenting with 3D printing on trucks so that goods can be built as they are being delivered to customers, while online clothier M-Tailor draws on the improved photographic power of cell phones to help its customers design, make and deliver shirts specifically configured to their unique physical characteristics.

- Acceptance of complexity as a business driver. In the past, complexity was viewed as something to be avoided at all cost because it added cost. Now, firms recognize that their customers are driving the demand for complexity. If a customer is willing to pay for something done in a unique way, the firm can make the customer aware of the hidden costs and dangers but ultimately, it needs to deliver. In part, the ability of the supply chain to deal with this increased demand for complexity is being enhanced by the new technologies discussed above.

- New competitive pressures. How a firm serves and interacts with its customers is being influenced by the experiences of its customers with other providers, especially Amazon. This has given rise to the “Amazon effect” - the impact exerted on both customers and firms by Amazon’s relentless emphasis on quickly connecting its customers to new and innovative solutions. Once Amazon rolls out a new service, its customers come to expect the same level of service from their other providers. For example, at the 2015 Supply Chain Outlook Summit, a supplier of industrial equipment explained that when one of its customers was told that there would be no customer service on weekends, the customer threatened to pull out of negotiations. The customer argued that if Amazon could provide support on the weekend, then the equipment supplier should also. Dealing with the Amazon effect often requires changes to the supply chain.

- New methods of dealing with customers. Increasingly, the customers of B2B and B2C businesses expect to be able to place orders and find information through various means, whether through brick and mortar retail locations, on-line or through smart phone apps. This “buy from anywhere, anytime and on any device” mentality has led to the emergence of the omni-channel experience. To a large extent, the success or failure of delivering on an omni-channel strategy depends on the supply chain system and its leadership.

- Recognition that cost is no longer enough. Traditionally, delivering a product or service at the lowest cost was the primary measure of supply chain performance. That view is now changing. As this author and others noted in the MIT Sloan Management Review in 2010, supply chains can achieve more than just cost reductions; they can offer improved security, innovation, responsiveness, sustainability, resilience and quality. To understand the competitive value of these other outcomes, consider the impact of Zara on the retail apparel industry. The fast fashion producer became a global powerhouse by emphasizing responsiveness with production near the markets it serves at a time when its competitors were focused on cost, and, as a consequence, outsourcing to low cost countries such as China.

- Customer demands for greater supply chain visibility. Customers, especially in North America and Europe, want assurances that their products are being produced safely and without adverse impacts. Companies such as Disney now recognize that they are accountable for actions taken anywhere in their supply chain, whether those involve first tier or fourth tier suppliers. That is one reason why Disney announced in 2013 that it was pulling production out of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ecuador, Venezuela and Belarus due to concerns over safety standards for supply chain workers in those countries.

When these and other changes are taken as a whole, what we see is a transformation of the supply chain from a necessary evil and source of risk to a strategic asset that enhances a firm’s competitiveness in the marketplace by offering one or more of the following three advantages:

- deliver goods and services faster, better and cheaper (the lowest form of competitive advantage);

- enable the firm to address customer needs that are currently being met poorly; and

- enable the firm to address customer needs currently not being met at all (the highest form of advantage).

The Traditional Supply Chain Leader

While that all sounds good, the biggest hurdle to completing this transformation is that many of the supply chain managers currently in leadership positions are not prepared to harness the capabilities of this new supply chain. In part, this is because many have not been formally trained in supply chain management.

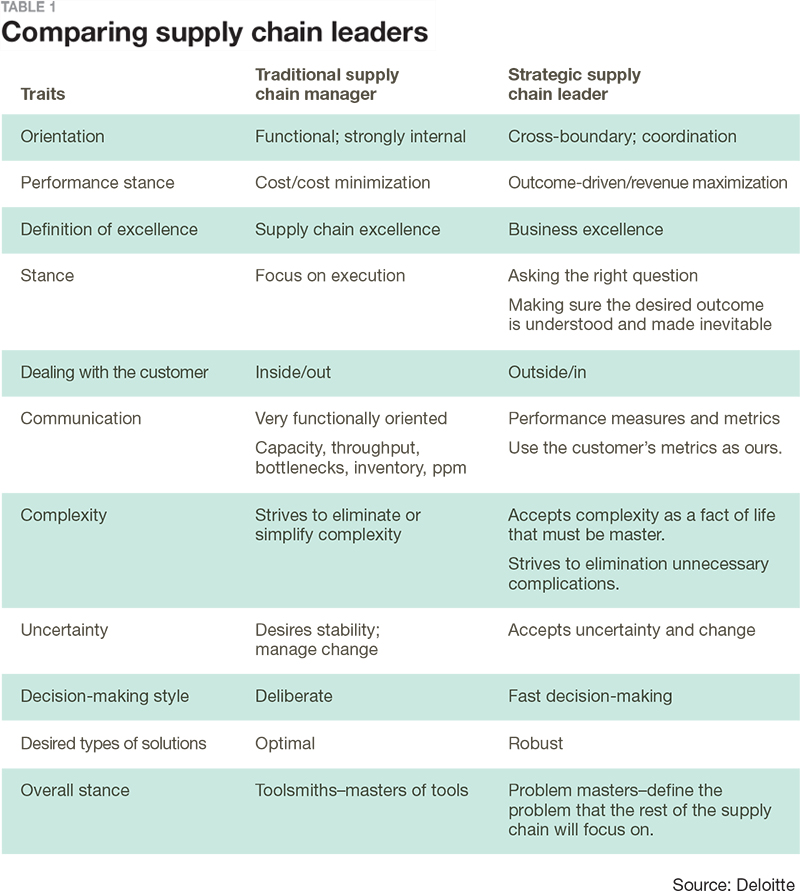

More importantly, these problems can be traced to their functional orientations and preparation - preparations that have imparted in them the traits below.

- Strong functional orientation. These are managers who feel most comfortable working with other similar people. Interactions with other functions are handled through hand-offs, best described as decisions that are “thrown over the wall” to other groups with little or no input from them.

- Strong focus on cost. Cost reduction is the universal benchmark. But just as no good deed goes unpunished, this can have unintended consequences. That was the lesson learned by one major farm equipment manufacturer after it implemented a world class Lean/Just-in-Time system with the stated goal of driving down cost. Unfortunately, a laser focus on cost reduction adversely affected the manufacturer’s ability to be responsive during a time when demand was greatly changing (thus hurting the company’s competitive position in the short term).

- Strives for supply chain excellence. The goal to develop a best-in-class supply chain on specific measurements, such as cost, may not necessarily result in better overall corporate performance, especially if the goals of the supply chain are not aligned with the strategy of the business.

- Strong focus on execution. This supply chain is focused on implementing decisions made elsewhere in the firm, without having any input or effect on those decisions.

- Speaks a language that is very functionally oriented. Current supply chain managers speak their own language, one that is rooted in terms like capacity, throughput, bottlenecks, inventory and ppm. This language hinders the ability of current supply chain managers to effectively interface with the other functions of the firm and with top managers who measure performance in different ways.

- Strives to simplify and avoid complexity. In the traditional supply chain, complexity is seen as something that adds cost and lead-time and must be resisted whenever possible.

- Deliberate decision-making. The traditional supply chain manager believes that it takes time to make decisions. Haste makes waste.

- Optimal solutions are the best. There is something “optimal” about an optimal solution.

- Stability. It is highly valued.

- Toolsmiths. Many current supply chain leaders are well grounded in solutions that they can quickly apply to any situation or problem. They are masters of ERP, MRP, DDMRP, Six Sigma, Total Quality Management (TQM), Theory of Constraints (TOC) and Lean/Just-in-time.

What we have here is a broad brushed view of the typical supply chain manager. But while these traits might help get things done, they are not the traits needed by leaders of the new strategic supply chain.

The Emerging Supply Chain Leader: Strategic in Focus; Outside/In in Orientation

The emerging supply chain leader - such as those we encountered in the “Beyond the Horizon” project and the one hinted at in the Deloitte supply chain survey - has a very different set of skills and orientations, namely those outlined below.

- Excels at managing at the interfaces. The new supply chain leader recognizes the need to work with other functions within the firm. Specifically, they must be prepared to engage with groups such as engineering, marketing, finance, accounting and top management. This engagement is bi-directional. On one hand, they need to understand the requirements of these other groups because their needs have to be translated into capabilities that the supply chain must provide. On the other hand, the new supply chain leader must be prepared to educate these other groups on the capabilities of the supply chain - what the supply chain can and cannot do. They must also be able to communicate how actions taken by these other groups affect the performance of the supply chain. For example, they must be able to show how promotions can adversely affect the ability of the supply chain to ensure that there is adequate stock on the shelf once the promotion becomes active. If a change in supply chain capabilities is required, then it is the responsibility of the new supply chain leader to communicate to the other areas how long it will take and what it will cost. In other words, the new supply chain leader must excel at educating, informing and coordinating.

- Focus on asking the “right” question, rather than on the “right” solution. This is where critical thinking shines. As Charles F. Kettering, the brilliant designer and engineer at General Motors, once said: “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.” Here, the supply chain leader is more interested in ensuring that there is a clear and concise understanding of the desired outcome, rather than focusing on a specific solution. This means ensuring that everyone understands what the goal is, and then soliciting the input of the various members of the supply chain to identify how best to achieve this goal. The solution becomes secondary to the desired outcome because it is driven by this outcome.

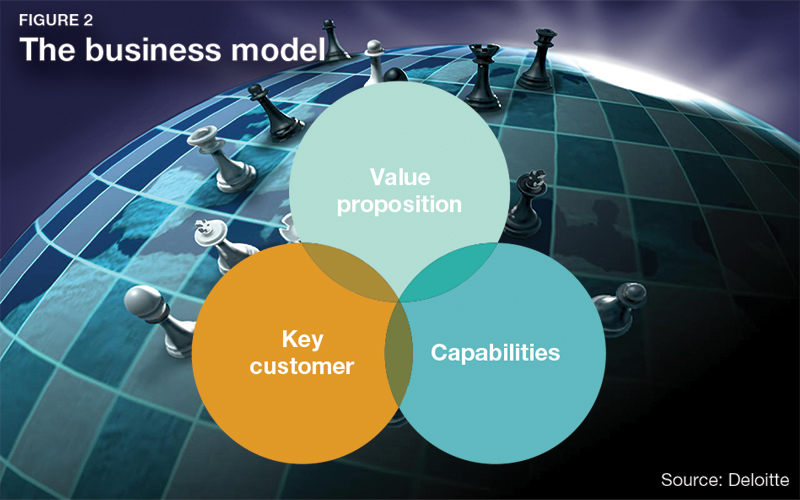

- Strives for business excellence, rather than supply chain excellence. Here, the goal is to help the firm better compete at the business model rather than the supply chain level. The business model, which can be viewed as a highly operational restatement of the strategy (see Figure 2), identifies three critical components that must be consistently maintained in alignment for the firm to compete:

- The key customer. The customer is the ultimate judge of what is produced. Here, the new supply chain leader must identify who it is that the firm is specifically targeting - whose needs will it try to profitably satisfy.

- The value proposition. This is what the firm offers to attract and retain key customers.

- Capabilities. These are the resources, skills, processes and assets that the firm draws on to deliver the value proposition that is expected by its key customers. It is here that the supply chain resides, along with corporate processes, measurement, capacity and corporate culture. The new supply chain leader understands that it is their task to ensure that what the key customers expect, what the firm has promised and what the supply chain can deliver are continuously in alignment over time.

Outside/in as compared to inside/out. A strategic supply chain manager views the capabilities of the supply chain through a different lens. The traditional lens is from the inside/ out, where the leader understands what the supply chain can and cannot do and tries to convince key customers that this is what they really want. The new, strategic lens is from the outside/in: It looks at what the key customers want and what type of outcomes they wish to achieve.

These new leaders understand that it is these key customers who drive the firm, its strategy and ultimately the supply chain. This identification with key customers takes its most immediate form in terms of how communication is implemented - through measures and metrics.

Effective at communicating with others in terms of performance measurement, measures and metrics. To effectively communicate within the firm, the new supply chain leader must recognize the importance of measures and metrics as communication. Measures and metrics, as noted by management experts Joan Magretta and Nan Stone, restate the business strategy and the business model into what each group or person must do to achieve this strategy.

Increasingly, we are recognizing that effective communication within the firm occurs at this level, not in terms of measures such as capacity, throughput and utilization. The new supply chain leader uses these measures to show how the actions of the supply chain can affect how others perform. Furthermore, in many cases, the new supply chain leader takes this emphasis on performance to a new level by adopting the customers’ own measures as their own.

When this occurs, communication is immediately enhanced between the supply chain and the customer because both are using the same set of measures. More importantly, supply chain impact can be seen immediately because these actions can be translated into how they affect the performance of the customer. Since both parties are using the same numbers (so to speak), the opportunity for conflict is minimized.

Recognizes the need for complexity but still strives to identify and eliminate complications. Because the new supply chain leader closely knows and identifies with the key customer, there is an acceptance of the need for complexity. Complexity is a trait that comes from the key customer and is something that the supply chain must be able to accommodate.

The leader does try to communicate the downside risks of complexity through a cost of complexity approach (see Figure 3). However, the leader is able to differentiate between complexity, which comes from the customer, and a complication, which occurs because of the actions of people within the supply chain.

As an example of a complication, consider the following situation. A firm has a short-term quality problem with a component supplier. To address the immediate issue, it modifies its manufacturing process to include an inspection activity.

The problem is eventually addressed but the inspection is not removed. This inspection is an example of a complication - something that plagues most supply chain systems. The new supply chain leader may have a purpose to add complications, such as increasing the number of backup suppliers, but these actions are often driven by the need to protect the system from disruptions and to improve resilience.

Recognizes and accepts the presence of uncertainty and change. Uncertainty is viewed as the natural state of things when it comes to making a decision. After all, you never have enough time; the information is never complete or sufficiently accurate; and something is always changing before you make your decision.

Strives for robust rather than optimal systems. Optimality is nice. However, in many cases, optimality results in fragile systems. That is, as long as things have not changed from the conditions that were used to derive the optimal solution, all is well.

However, as soon as something changes in the environment, the optimal system sputters. Instead, the goal should be a robust system, one that may not generate optimal performance but is able to respond to changes without extracting a severe penalty in performance. Robust systems are the natural complement to the preceding trait.

The focus is on the future. In this new environment of change and uncertainty, the past is viewed as a lesson to be learned, and not as the basis for punishment. As one manager in the “Beyond the Horizon” project put it: “The past is something you cannot do anything about. Learn from it; get over it; focus rather on the future.” That is the attitude assumed by the new supply chain leader.

This focus and concern about the past is also reflected in planning. The new supply chain leader recognizes the importance of that basic supply chain dictum - today’s supply chain is the result of investments made in the past; tomorrow’s supply chain will be the result of investments made today.

Fast decision making is the key. In this environment, you do not have the time to wait until changes shake out. Rather, you have to make decisions quickly and be willing to live with the fact that you will be wrong on occasion. This is becoming the natural state of affairs.

As one manager put it: “You make decisions quickly, you fail fast, you learn quickly, you move on.” This was best illustrated during the “Beyond the Horizon” project by one interview that took place at a fast fashion goods operation located in the Midwest.

The manager who was leading research team members on a plant tour stopped to point out a new $1.7 million line. He asked the research team to guess how long it took to go from problem awareness to the time that this line was up and running.

The team members answered with numbers ranging from two to three years. The answer: Seven months. When questioned, he brought out the key lesson: If the company had waited to make sure that the issue driving the need for the investment was real, it would have been too late. A new, faster method of decision-making is demanded.

The Challenge

The evidence, as summarized in Table 1 is clear. While there will always be a demand for tacticians and fire fighters, the new strategic supply chain needs a different type of leader, perhaps a Chief Supply Chain Officer (CSCO) who is well prepared by skills, temperament and preparation to sit at the same table as the CEO, CIO, the CFO and other similar leaders.

And that is where the real talent crisis lies. That is because generators of the current supply chain talent, such as professional societies like APICS, ISM, CSCMP, firms and educational institutes at the community college, college and university levels, are for the most part structured and organized to deliver the traditional supply chain manager. Their focus is on tools and content.

While those are important, they are not enough - they can be viewed as the cost of playing the game. What makes future supply chain leaders so different are their thought processes and approaches. They are coordinators and orchestrators; they educate and communicate; they see the supply chain not as capacity but as capabilities (what the supply chain can do well and what it does poorly); they focus on the desired outcomes rather than on the solutions.

Finally, they recognize that ultimately the supply chain is strategic, not because it is the best example of Lean or Total Quality Management, but because it supports the firm’s value proposition and helps the key customers succeed. The challenge for the current generators of supply chain talent is to develop a system that can create such leaders. However, for those firms and organizations that can meet this challenge, the future is indeed bright.

About “Supply Chain Management: Beyond the Horizon”

“Strategic Supply Chain: Beyond the Horizon” (SSC:BTH) is a long-term project aimed at identifying and exploring emerging issues in supply chain management both domestically and internationally. This project, jointly sponsored by department of supply chain management, the Eli Broad School of Business and APICS, has over a three-year span studied over 60 leading supply chain management organizations. The results and insights obtained from this project have been fine-tuned and tested in a series of focused workshops. This project has been led by David Closs and Pat Daugherty of the Department of Supply Chain Management at Michigan State University.

Related Article The 2016 Supply Chain Top 25: Lessons from Leaders

Article Topics

ASCM News & Resources

Supply Chain Stability Index sees ‘Tremendous Improvement’ in 2023 Supply Chain Stability Index: “Tremendous Improvement” in 2023 The Right Approach for Supply Chain Education The reBound Podcast: Innovation in the 3PL supply chain Supply Chain’s Top Trends for 2024 Require Talent Investment for Success Resilience Certificate Now Available from ASCM ASCM conference highlights importance of geopolitics in the supply chain More ASCMLatest in Supply Chain

TIm Cook Says Apple Plans to Increase Investments in Vietnam Amazon Logistics’ Growth Shakes Up Shipping Industry in 2023 Spotlight Startup: Cart.com is Reimagining Logistics Walmart and Swisslog Expand Partnership with New Texas Facility Nissan Channels Tesla With Its Latest Manufacturing Process Taking Stock of Today’s Robotics Market and What the Future Holds U.S. Manufacturing Gains Momentum After Another Strong Month More Supply Chain