How to Deal With Company Culture “Eating” Your Supply Chain Strategy

Too often, best-laid plans are nullified by company culture, a force that supply chain managers do not anticipate, and while culture is often cast as a source of inertia and un-thinking rejection of change, it plays an essential role in executing strategy.

Situations That Occur in Supply Chains

Consider the following, not too uncommon situations that occur in supply chains all the time.

A company had been very successful in implementing Lean systems. Its employees had embraced the Lean approach to operations and the results showed in the bottom line.

Yet, management was becoming aware that Lean was now a given in the industry. Innovation, it turned out, was becoming the new order winner.

Consequently, management worked hard at explaining to the firm’s employees the need to change the focus to innovation.

It introduced an extensive training program; new measures and metrics were deployed; an innovation grant program was also launched. After over two years, management called in an external group to assess the progress.

The results were disheartening: Innovation had not taken root. On the contrary, the employees continued to embrace Lean and rejected innovation as a fad.

Management’s attempts at implementing a strategy of radical innovation had been subtly transformed by the system into a strategy of incremental innovation - something that was consistent with Lean.

In another case, a firm that had been successful with responsiveness and quality as the foundations of its corporate strategy decided to outsource a major component to a supplier to keep costs under control. The firm selected a supplier with an established reputation for cost leadership. Initially, the relationship worked well and costs fell. But as the relationship continued, tensions appeared.

Decisions were made by the supplier that was consistent with its commitment to cost management but were at odds with the way that its customers competed in the marketplace. Over time, the thin initial contract was replaced by an increasingly thicker and more comprehensive contract, until everything in the relationship was subject to evaluation and rules. Ultimately, the relationship was terminated, leaving bitter feelings in both parties.

In both of these cases, we see firms seeking to improve their competitive positions, but failing to achieve their desired outcomes. Both organizations conducted postmortems and identified the same culprit - culture.

These experiences are not unique to these two organizations. They can be expected to occur whenever organizations try to change their goals, their means of achieving these goals, or both simultaneously. In these cases, organizations can expect to encounter resistance from their cultures, especially if they have been successful in the past. Not surprisingly, management in these organizations tends to see culture as an obstacle and liability - something that is irrational and difficult to deal with.

These views are often best summarized with the adage that “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”, a phrase originated by Peter Drucker and made famous by Mark Fields, President at Ford, is an absolute reality! Any company disconnecting the two are putting their success at risk.

This view captures how managers feel when they discover that their best-laid plans are nullified by a force that they did not anticipate nor fully understand. The problem with blaming culture is that this position is often misguided and wrong.

This is a biased view of course, as the role of culture in instances like these is usually being ascribed by those who advocated the change in question in the first place - something has to take the blame and culture is a convenient scapegoat.

A more balanced view might see culture as a source of healthy skepticism, a stronger dose of which might have saved some well-known companies from commercial disaster. However, neither of these views fully appreciates the role of culture in a firm, why it is essential, and why it is actually the manager’s friend.

In this article, we draw on a body of research, two examples of which are described in the sidebar below. What we have found in a diverse range of examples is that to understand and work with culture in times of change, it is necessary to break with conventional wisdom in many areas and dispel several management myths.

In this article, we will focus on answering the following three questions:

- What is culture, why is it a potentially valuable asset to the firm and the supply chain, and how is it similar to strategy?

- When do culture and strategy clash and why?

- What options are available to managers when facing by cultural conflict?

Ultimately, we hope that our findings will lead to a better and more balanced view of culture and its role in the firm and the supply chain. Culture can be a powerful asset and force, if properly understood and used correctly.

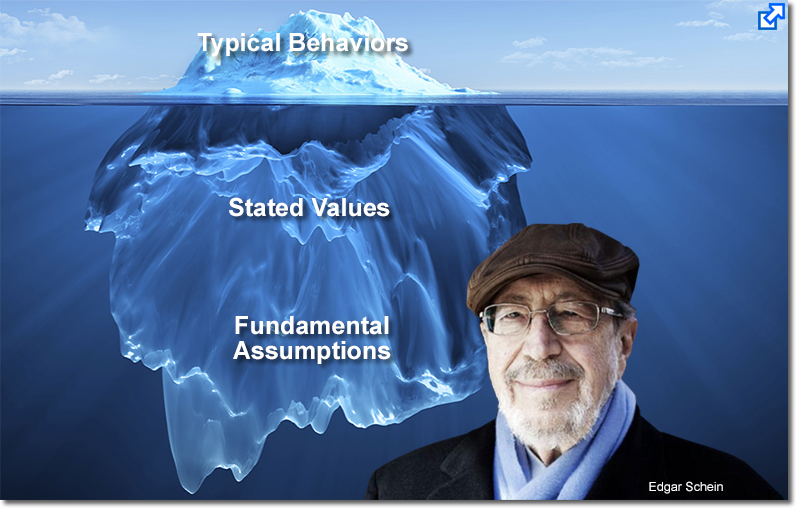

Understanding Corporate Culture

Corporate culture has been defined in various ways, including “the collective values, beliefs and principles of the corporation,” and, more simply: “what people do when the boss is not around.”

However you define it, corporate culture answers two critical questions:

1) what is important to the organization; and,

2) how employees should most appropriately go about achieving these.

These answers are the result of a learning process that develops over time as people see what has and what has not worked.

For organizations such as Pixar, the corporate culture informs employees that their goal is telling good stories that they, the people who work for Pixar, would pay to see and that the method, the how, is through leading edge computer animation.

Culture develops over time, gradually, and in ways that are often difficult to see. In the case of Pixar, the critical and financial success of films such as Toy Story, The Incredibles, Finding Nemo, and Ratatouille has served to reinforce the solutions being practiced to the what and how questions. Culture is taught or passed on from existing members to incoming members. It defines the knee-jerk reflex of the organization.

That is, when faced by a challenge, culture shapes how the corporate members will respond. It also defines the expectations of the firm and its members. Organizations such as the New England Patriots, the Metropolitan Opera, LEGACY Supply Chain Services, the U.S. Marine Corps, and Pixar expect to do well because they have done well in the past. Culture is potentially a powerful force in a time of change that is, unfortunately, surrounded by some important myths.

Management Myth: Show Them A Better Way And They Will Embrace It

The following is a situation we observed during the course of our research that is present in many organizations. Top management has determined that the existing ways of doing things are no longer adequate and they find a new and better way. For example, the emphasis on mass production is to be replaced by a focus on Lean. Resources are developed to support this new focus. Extensive education takes place within the organization.

The new approaches are demonstrated and shown to be “better.” The participants listen politely; they participate in exercises designed to demonstrate the application of the new approach and its impact. Yet, when the trainers and managers go away, the participants don’t apply these new approaches consistently.

Rather, they apply only what is compatible with the old ways of doing things. Change may superficially seem to have taken place, but the results are often less than expected. What is going on? The answer lies in the sometimes conflicting, sometimes complementary roles of strategy and culture.

For people to act, they must know how (to do the task) but also the what (the purpose of the task or the desired outcome). The participants in the above example knew how to apply the new techniques. However, they lacked the second component - the what, or the belief that those techniques would achieve the right results, as they understood them. Belief is not something that can be easily taught, especially if it conflicts with the lessons of experience and the reinforcement of one’s surroundings and peers.

The reality is that people’s beliefs are not a good additive. They cannot simply layer different approaches on top of each other. This is very important when the desired outcomes are changed. Under such conditions, people will accept only those practices that are consistent with what they have done in the past (and that they know works). If you want them to totally change how they do things, then an un-learning process must first take place. New and better is not very compelling when the existing state is demonstrably good enough (and when the employees still see adequate opportunities to successfully apply the old ways of doing things).

If management wants to replace the old with the new, they must first thoroughly discredit the old approach before the new approach can take root. This can be done in several ways, including a company crisis (the most direct way of showing that the old ways no longer work). Alternatively, we can remove the peer reinforcement that gives legitimacy to existing models. This is one reason that we see firms replace long-time employees with new ones who are not aware of how things were done in the past.

The problem here is that many strategic initiatives are seen by senior management as a “how” problem; simply alternate ways to accomplish the same goal. As a result, they expect persuasion and training to be sufficient. However, when these directives are passed down to lower tiers in the firm they become revised goals for different functions and departments. What we found in those situations is that new methods are used selectively, and only to the extent that they support the existing understanding of “what” is to be accomplished.

Management Myth: Culture And Strategy Are Natural Enemies

Remember that phrase, culture eats strategy for breakfast? Culture and strategy are often portrayed as natural enemies because the strategy requires change and culture often resists it. As a result, management regards culture as a sort of irrational resistance to change. This is a misreading of the situation. At the root of such conflicts is the core fact that both strategy and culture provide a rationale for “what” is to be done: They are both theories of cause and effect that tell us that if we behave in certain ways, good results will follow. When strategy and culture provide different prescriptions, they cannot coexist.

When viewed from this perspective, culture becomes seen as a liability. Yet, this fails to acknowledge the positive aspects and the tremendous value of culture to management. Although organizations can be surprisingly obstinate in rejecting “improvements” that are not consistent with their collective sense of purpose, the same organizations can be just as surprisingly receptive to even radical innovations that are consistent with their purpose. The reference to Pixar in the introduction can be seen as evidence of this at work. This is a powerful effect that managers can make work to their advantage.

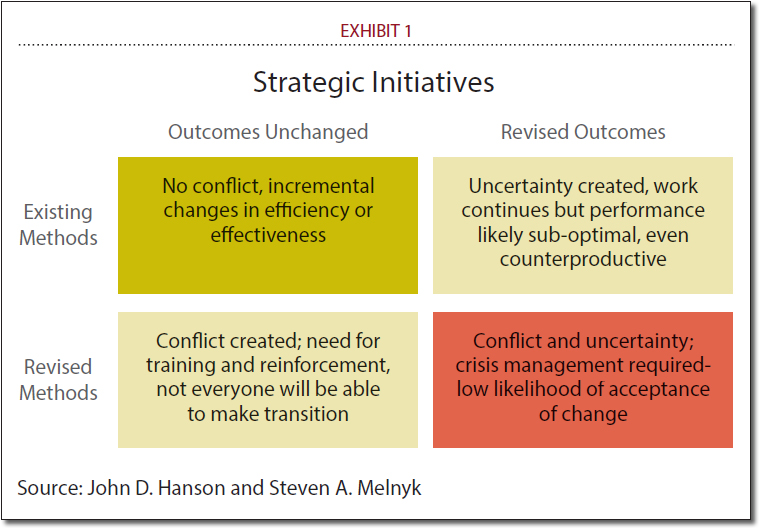

If we want to change initiatives to be effective we need to understand their characteristics and how these interact with cultural forces. Although it is somewhat simplistic, we can characterize strategic initiatives on a 2 x 2 grid (where the columns deal with the objectives or the “what” and the rows with the processes or “how”).

When both the what and the how are unchanged, we are in the green quadrant of incremental improvement. Traditional approaches such as training and use of performance-based incentives work well here.

Things begin to deteriorate when one of the key elements must change, and with strategic change it is often the case that both must change, placing the firm in the red zone. Both conflict and uncertainty are created when employees must adapt to a new sense of purpose and learn new skills at the same time. Not all employees will be able to make the transition; the motivation to abandon what has worked so far, and to adopt new approaches is normally only provided by a serious crisis. It has been suggested that to achieve transformative change it may be necessary to create a crisis for the purpose, and it is not unheard of to fire the key employees most closely associated with the status quo to send the message that business, as usual, is no longer acceptable.

Interestingly, both of our studies (see sidebar below) took place in the red quadrant; ironically management did not recognize this. In the innovation initiative, management thought that only a change of outcomes was needed and that a modification of performance measures would stimulate the appropriate behavior. The changes in the essential purposes of action were overlooked. In the study of Lean process implementation, management assumed that there was no change in purpose and that education in superior methods would be sufficient. There was however a subtle difference in purpose (the difference between the Lean and the Mass Production mindset) that compromised the results. In both cases, management was surprised when they learned that the changes had not taken root - even though the reports indicated success.

Management Myth: Don’t Tell People How To Do Their Jobs - Tell Them What You Want Done And Get Out Of Their Way

Conventional wisdom tells us that good managers don’t tell their employees how to do their jobs. Instead, they communicate what is to be done and let the employees figure out the best way to accomplish it. This can be extremely effective, but relies more heavily than we often realize on organizational culture. Every employee has to make multiple decisions in a day, often requiring tradeoffs in one direction or another.

Culture supplies the guidance that tells them to compromise this rather than that. In the absence of culture, managers would have to take on an unbearable level of micro-management or suffer from an organization of independent actors all working at cross-purposes. In many ways, culture in an organization is like friction in the physical world: a great impediment at times, but you couldn’t do anything without it.

Culture plays a key role in guiding behavior. However, in a transition period where culture no longer supplies the “right” rationale, its role in decision-making must be suppressed. This can be accomplished by specifying in detail how the work is to be done - as in dictating the activities to be performed. This change in approach must be accompanied by some unfamiliar and sometimes uncomfortable adjustments.

In particular, it is no longer appropriate or effective to measure and reward employees for results. They must be rewarded for their effort and compliance, and responsibility for the results must fall to higher-level managers. Not only is this more work than most managers are accustomed to, but it also comes at a time when management is likely to be fully absorbed by changes in the external environment. Yet, it is necessary until the culture can be brought back into alignment with the changed strategy.

Bringing Culture and Strategy Into Re-alignment

If we want to continue relying on culture to play its valuable role in guiding behavior, and if the old ways of doing things are no longer adequate, then we must change the culture. We must act as leaders. As Edgar Schein, the father of research into corporate culture puts it, “managers work within cultures; leaders work on culture.”

As we have already stated, there are two key obstacles to changing culture. The first is that it is not sufficient to come up with a “better” strategy; it is necessary to displace the existing one. The more successful the firm has been, and the longer it has been successful, the harder it is going to be to change the culture. Culture takes time to emerge, and it takes time to change. Consider a bonsai tree; when we want a plant to grow in a way that does not come naturally to it, we have to wire every branch and twig in place.

Eventually, we will be able to remove the wires, but not until the plant has adapted to a changing environment. The same holds true for an organization. A genuine crisis will speed this up enormously: a bankruptcy filing and massive layoffs will generally get the message across that what was good enough before is no longer adequate. However, we would prefer not to let things get to that point, so the art of management is to make necessary changes before the crisis hits.

The second obstacle is that culture is absorbed from and reinforced by peer groups so that change cannot take place one convert at a time; it must be across the board. One way to accomplish this has already been mentioned; that is to create a sense of crisis by firing key individuals who are not adopting the new approaches. As one of the managers interviewed put it: “There is nothing as useful as an occasional public execution to drive home the point that things are changing.” This not only puts the entire organization on alert that things have changed, but it also erases part of the culture and removes some of the peer reinforcement that gives it staying power. While effective, this carries costs and risks, so there is interest in working around culture until the necessary changes can take root.

Culture and Strategy in Supply Chain Relationships

Our view of culture to this point has been mostly internal to the firm, but our suppliers and other supply chain partners have cultures of their own. If implementing strategic change within an organization is difficult, we should not expect it to be any easier when it requires the involvement of these partners. Suppliers, and to some extent, customers act as agents in many of the same ways that employees do. Earlier we described culture as what people do when the boss is not around. In supply chain relationships, the “boss” is rarely around, so in the case of our partners, we are even more dependent on culture to guide day-to-day activities.

This creates an additional set of criteria for selecting supply chain partners. Most partner selection efforts are devoted to ensuring interoperability: the capabilities must match, the systems must communicate, we must be able to read each other’s data. We now have to recognize that a cultural match is also an important criterion for selection. Otherwise, the organization will be burdened by high transaction costs as it tries to micro-manage its partners. This was the case in the introductory example where the chosen supplier did not share the customer’s bias towards quality and responsiveness.

In the past, we have selected partners on the basis of economics, capacity, and capability considerations. To these factors, we must include culture. It can be argued that the longer the desired relationship and the more important the outcomes to be generated by the relationship, then the more important the culture card becomes. Selecting partners on the basis of a cultural match is not easy as we don’t have any sort of personality type indicator for companies.

A meeting of the minds of the top executives is a good start. It is important to consider the historical strengths of a potential partner as those will most surely be the basis of its culture - regardless of what its management is currently saying. It will also be useful to consider whether the potential partner has a history of success in working with other companies, as culture tends to foster a sense of “us versus them” that may have to be overcome for a partnership to be effective.

In times of strategic change, it is just as necessary to manage the culture change in the supply chain as it is within the firm. In some ways, it is easier to change partners than to change employees, and it may sometimes be necessary to “fire” a supplier if they don’t get it, even though they may be good performers otherwise. This will no doubt be noticed by other partners and may serve the same role as firing employees in terms of signaling a crisis and expediting a shift in culture.

Just as with employees, if the choice is to work around a partner’s culture until it can change naturally, the approach is to micro-manage them with detailed contracts and close monitoring, accompanied by incentives to persuade them to behave in the right way. However, unless the organizations are driven by a similar purpose, the results are likely to be both surprising and disappointing. For one thing, micro-managing is harder across company boundaries, and for another, most culturally-driven behavior is aimed at ensuring the survival of the community and is unlikely to encourage collaborative behavior with outsiders.

Culture: Bringing Closure

We have drawn from our research studies to identify the origins and nature of organizational culture so that we can understand how it helps or hurts strategic change management. The lessons learned to extend to the broader supply chain, so we raise the question of whether the cultural element has been considered as part of plans to reconfigure the supply chain.

Our research tells us that resources must be dedicated to either selecting partners on the basis of a cultural match, or to work around a potential mismatch. Culture is important but often overlooked. Consequently, we often find that culture does eat strategy for breakfast. However, with the appropriate knowledge and management intervention, we can make culture serve the strategy, rather than eat it.

The Research

Our findings derive in large part from two in-depth, multi-year research projects conducted at Michigan State University. The studies were initiated independently and set out to address different questions but converged nicely at the intersection of culture and strategy. In both cases, however, the research questions were motivated by a persistent problem that underlies much of the literature on strategic management: Initiatives that should have improved performance routinely do not, even when local level metrics suggest that they are working.

The first study set out to follow the implementation of a top-down strategy initiative in a corporation made up of multiple, relatively autonomous business units. Senior management had come to the conclusion that their previous focus on cost leadership and operational efficiency was a dead-end strategy in which they would never prevail against global competition. Instead, they decided to focus on value-creating innovation and set in place new metrics and incentives to move the corporation towards new goals. On the surface, the effort appeared to be a success since the revised goals were being met. However, there was a sense of frustration that these results weren’t translating into improved sales or profits. Our study, based on extensive interviews up and down the chain of command, confirmed this.

The second study was designed to study mechanisms of organizational learning and documenting the attempts to implement Lean production techniques in a group of affiliated companies through kaizen events. The purpose of the initiative was to provide employees with an expanded toolbox with which they could improve operational efficiency. The goal of the study was to understand how, or if, these enhancements became institutionalized. In what amounts to a mirror image of the previously mentioned study, this situation was apparently in the lower left quadrant, where new techniques were to be learned and used to achieve overall system efficiency.

In practice, however, few of those involved realized that there was a subtle difference in presumed purpose between those sponsoring the effort and those implementing it. The former was pursuing an approach of system optimization, while the latter was constrained by their situation and experience to pursuing local optimization. As a result, the situation was more appropriately placed in the lower right quadrant, with similar issues to those already described.

What we observed along the way was very similar to what we saw in the first study. Impressive results were reported on measures such as set-up time reduction and reduction in cycle stock through pull systems, yet there was no measurable effect on bottom-line measures. What was happening was that shop-floor level employees were working at cross purposes with the strategic intent.

As an illustration, set-up time reduction was pursued because it was seen as a way to reduce indirect labor hours, not as a way to reduce batch sizes. When the possibility was raised of further reducing setup time by increasing indirect labor hours (double-teaming for example) the idea was rejected because it was inconsistent with the perceived purpose of the exercise. The effect was similar to giving someone a screwdriver and seeing them use it as a chisel; something was lost in translation.

In the end, both studies showed examples of the typically paradoxical results observed in business. The reported metrics showed positive progress, but deeper analysis showed that both initiatives were, in fact, failures in the sense that they did not result in meaningful or sustainable changes in how employees actually worked. Both of these failures could be cited as examples of resistance to change, or of culture defeating strategy, but that is a limited view of what is going on. We feel it would be more accurate to say that they failed because management failed to appreciate the true nature of the changes they were trying to implement (bottom right quadrant) and failed to manage appropriately.

About the Authors

John D. Hanson, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management at the University of San Diego. He can be reached at [email protected].

Steven A. Melnyk, Ph.D., is a Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Management in the Department of Supply Chain Management, Michigan State University. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related Article: Organisational Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner

Article Topics

LEGACY Supply Chain Services News & Resources

Outsourcing eCommerce Fulfillment to a 3PL Rapidly Improve the Performance of Your Warehouse Logistics 20 Warehouse & Distribution Center Best Practices for Your Supply Chain Warehouse Contingency Planning Template 7 Last Mile Logistics Delivery & Ecommerce Trends You Don’t Want to Overlook Increase Inventory Visibility across Your Supply Chain and Optimize Omni-Channel Fulfillment Omni-Channel Logistics Leaders: Top 5 Inventory Insights More LEGACY Supply Chain ServicesLatest in Supply Chain

Microsoft Unveils New AI Innovations For Warehouses Let’s Spend Five Minutes Talking About ... Malaysia Baltimore Bridge Collapse: Impact on Freight Navigating TIm Cook Says Apple Plans to Increase Investments in Vietnam Amazon Logistics’ Growth Shakes Up Shipping Industry in 2023 Spotlight Startup: Cart.com is Reimagining Logistics Walmart and Swisslog Expand Partnership with New Texas Facility More Supply Chain