Framework for Safety Excellence: Lessons from UPS

UPS believes that there is no room for unsafe work practices in any aspect of its operations. At the base of this framework is personal value—a commitment by every employee to the safety system.

On a visit to UPS’s Worldport facility, which sits on 600 acres in Louisville, you would see why people call it one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

At the heart of the company’s global transportation network, this sophisticated mega hub sorts approximately 416,000 packages per hour over 115 miles of conveyor belts. On any typical day, the facility unloads 1.2 million packages from all around the world and then loads the sorted packages back onto more than 130 outbound flights within just five hours.

UPS seamlessly choreographs all movements with an objective of minimizing delays, flaws, or disruptions. An internal research team estimated that the Worldport facility had one mis-sort for every 4,826 packages that flow through, which roughly translates to 99.9998 percent accuracy.

At Worldport and at other UPS facilities, every employee attends a pre-work communications meeting, which always concludes with a safety tip. Safety is a core value to UPS, and there is no room for unsafe work practices. Why does UPS commit to high safety standards? How does the company encourage the involvement of all employees in safety activities?

This article seeks to answer these questions. We also offer some valuable “lessons learned” from the UPS experience for companies in other industries to consider. Finally, we outline the broader supply chain implications of a comprehensive safety initiative.

The importance of considering safety issues when designing products, processes, and supply chains can be seen from a negative perspective—that is, the many examples of what can happen when safety is compromised.

The 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan that put tremendous pressure on nuclear facilities, the 2010 mining accident in Chile, numerous product recalls in the toy industry, the BP oil spill, and Toyota’s unintended acceleration case. All of these examples point to the importance of safety. As with firms that are exemplars in sustainability excellence, the companies that are exemplars in safety excellence tend to be proactive, not reactive. This article focuses on one such exemplar of safety: UPS.

Building Excellence Through a Safety Framework

Even though UPS has always kept a keen eye on safe operations, it did not formalize its safety system until 1995. (The accompanying video gives a quick overview of UPS.)

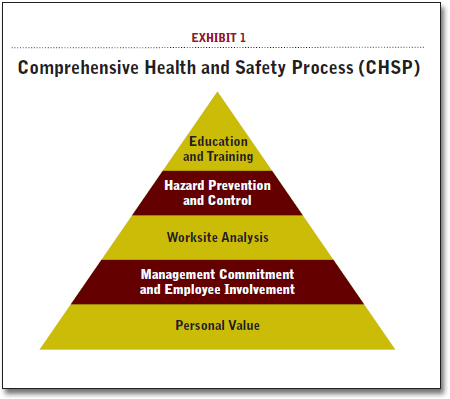

At that time, insurance agencies in Maine almost ceased offering workers compensation insurance for all businesses due to the high rate of injury cases in the state (more than twice the national average). Instead of dropping the coverage, the agencies approached the area’s largest employers to help develop a plan to reduce the number of injuries. It is from this simple instance that UPS launched a new initiative called the Comprehensive Health and Safety Process (CHSP), which set the company on its journey towards preventing accidents and reducing injuries.

CHSP was established using a pyramid as an enabling model (see Exhibit 1). The pyramid was chosen because of the structure’s stability, which is symbolic of the overall importance of a safe working environment.

At the base of the pyramid are personal values, which are the values that individual employees have towards safety norms. These individual values form the core components of the safety system. Moving up from the base, the CHSP pyramid includes management commitment and employee involvement, worksite analysis, hazard prevention and control, and safety education and training.

The safety process must be unwavering even in difficult times (bad weather or high production demands). In fact, it is during these times that even more focus needs to be placed on the safety process. UPS achieves this by making safety a core personal value of its employees. The reason: while priorities can change, core values never do.

The idea that the safety system should center on the individual is based on the premise that once safety becomes part of the individual’s value set, it will underlie all subsequent actions as the default expectation. By focusing on individuals first, the responsibility and control of a comprehensive safety process rests with employees, not management. The common understanding is that safety starts at a personal level, and is therefore everyone’s responsibility. CHSP empowers workers, via safety committees, to be responsible for all aspects of safety. The importance attached to the individual’s role is evidenced by a comment from a senior-level manager, who noted that “employees are 90 percent of the solution.”

Support from the Top

While making safety a personal value is essential, safety also must be a core value to the organization. To that end, UPS’s Senior Vice President of U.S. Operations convenes a meeting twice a year with the company’s senior operations managers to discuss nothing but safety. That type of emphasis from senior leaders is necessary to make safety a part of the organization’s culture—a true core value. UPS recognizes that safety has to start with senior management and must be embraced across all levels of the company.

The Comprehensive Health and Safety Process is called a process and not a program because unlike programs that tend to start and stop, a process tends to evolve. One example of that evolution was the change to the fundamental base of the CHSP pyramid. In 1995, the base was management commitment and employee involvement. In 2004, the base was changed to personal value to elevate safety above all operational concerns.

Once the individual focus is established, there is a need to include decision makers from all levels of the organization. This leads to the creation of the second tier of the pyramid that addresses employee involvement and management commitment. A typical CHSP committee consists of 10 percent of the workforce. Companywide, UPS has trained and deployed 40,000 CHSP members.

The combination of front-line employees and management focusing jointly on safety reinforces its overall importance, while offering a mechanism whereby all activities can be refined to advance safe working habits. The actionable component of this tier lies with the safety committees, where management and non-management representatives interact on a regular basis to address any issues that arise.

The role of management is not to dominate the safety committee process, but to support it. Management shows this support by allowing the committee time to get safety activities completed and offering assistance in getting solutions accomplished. Beyond the meetings, managers are required to sign a Declaration of Management Commitment, whereby the manager formally accepts the fact that wellness and safety are at the forefront of the operational decision process and that there is an expectation for zero accidents/injuries to occur under her or his watch.

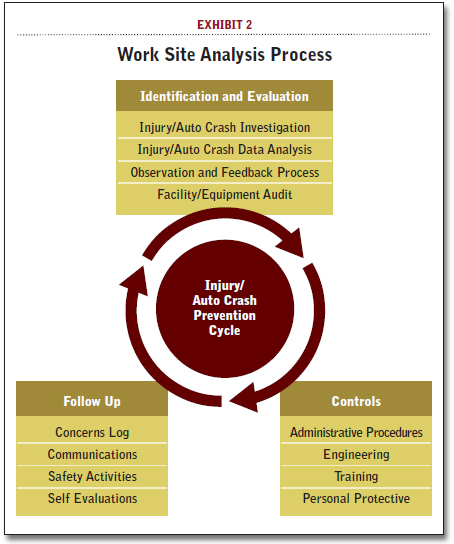

The next level of the pyramid is work site analysis, which is the formal examination of injuries and auto crashes, observations on work methods and techniques, and facility/equipment audits. It is in work site analysis that the company really begins to show its true colors. As one manager noted, “UPS is really just an engineering company that happens to deliver packages.”

The formal investigation and analysis of all unsafe instances affords the opportunity to look for any root causes so as to eliminate their recurrence.

A quick review of the CHSP Committee Member Handbook demonstrates the importance that UPS places on work site analysis; approximately one-third of the document is devoted to how instances will be calculated, investigated, evaluated and corrected (see Exhibit 2).

Company representatives familiar with CHSP universally noted that this in-depth analysis enables employees to quickly address and correct unsafe activities.

The company’s formal description of the worksite analysis process is as follows.

Worksite analysis is the component of the Comprehensive Health and Safety Process that assists a committee in developing safety activities to address injuries and auto crashes in their work area.

The analysis helps them analyze injury/crash data and formulate a plan of action associated with the most frequent and most severe incidents.

Worksite analysis uses many tools.

The primary ones include past injury/auto data, injury/crash prevention reports, facility audits, an employee concerns log, and observation and feedback process.

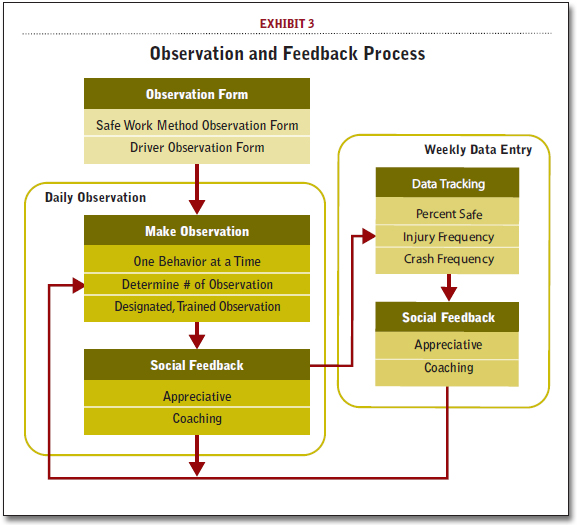

(Exhibit 3 depicts the observation and feedback process.)

To conduct a thorough worksite analysis, each committee is provided with a planning tool in an Excel workbook containing two and a half years of injury and crash data. The committee uses these workbooks to analyze the data and drill down to the most common and most severe injuries and crashes for their facilities, and by job function. The workbook provides claim details so that CHSP committee members can determine trends as to when injuries and crashes occur, factors that contribute to them, or even road conditions at the time of a crash. Once the analysis is complete, it serves as the basis for a 15-month action plan.

The next layer of the CHSP pyramid deals with hazard prevention and control, which is the mechanism for generating potential solutions to problems outlined in the analysis. The solutions process is captured in a “concerns log,” the safety committee’s tool for demonstrating that issues are being addressed. The log includes all the specifics of the concern—to whom it was assigned, the scheduled resolution date, and the actual date it was resolved.

Beyond the concerns log, the company has invested considerable time and resources in the direct observations of safe work methods. Employees are directly observed by management and non-management while performing the required job tasks. They are then provided positive feedback on their methods. The goal is to reduce the likelihood of an injury or auto crash occurring as a result of not performing the job correctly.

The key to the observational method is that feedback be in the form of both reinforcing (motivational feedback) and coaching (formative feedback). This dual nature of the feedback ultimately results in reinforcing the behavioral part of the individual’s personal value set towards safe practices, confirming why personal value is at the base of the pyramid. In 2010, UPS conducted more than 135 million work observations in its effort to prevent injuries and auto crashes. The company believes that when coupled with the employee mentoring program, the next evolution of CHSP will prove even more effective, and possibly result in even fewer unsafe incidents.

Safety education and training is at the top of the pyramid. This component not only addresses employee safety expectations, but also promotes overall wellness of employees and their families. Education and training represent the culmination of all other pyramid principles, wherein each employee now has all the tools necessary to enable him or her to work safely. UPS has mentoring programs to help prepare new hires for the job.

These programs focus on four functional groups: inside employee, delivery driver, feeder driver (tractor/trailer), and CHSP co-chair. Non-management employees lead the process in each mentoring component. In addition, each program provides training for the mentors in their areas of expertise and in soft skills. The inside employee and delivery driver mentoring programs, for example, have specific topics discussed daily for six weeks. The idea is for the new employee to learn a new topic and establish a relationship with a senior employee on a daily basis. All of the mentoring programs are tracked and audited.

In addition to the workplace safety activities, UPS emphasizes overall wellness. The company provides information and assistance on issues such as nutrition, smoking cessation, and exercise programs. Worldwide, UPS has more than 4,000 CHSP committees and virtually every committee has a wellness champion who educates the workers and their families on health-related topics. Essentially, the company is willing to help employees lead healthier lives, viewing these programs as investments in productivity.

In short, CHSP is a comprehensive safety process with a simple goal: Having UPS employees work in a zero-incident environment. Overall, the safety process has been extremely effective. Injury frequencies have been reduced by over 92 percent since the development and implementation of CHSP in 1995. These results have been realized throughout the organization. For example, the Aurora, Colo., facility achieved a 74 percent reduction in auto accidents, with serious auto incidents (called Tier 3 within UPS) decreasing to zero in 2010. Additionally, lost-time injuries at Aurora have decreased over 85 percent from 2006 to 2010.

In Greensboro, N.C., employees on the evening shift recently celebrated a milestone of 100,000 safe work days. That group of 400 employees has been working for over a year without a single lost-time injury. These results are not uncommon as the Comprehensive Health and Safety Process continues to be improved.

Building on Lessons Learned

UPS’s experience with the CHSP program has yielded some important “lessons learned”—lessons that may well resonate with companies in other industries pursuing their own supply chain safety initiatives. Six particular lessons deserve mention here:

1. Successes, both large and small, need to be recognized. UPS has learned that safer employees are also more productive employees. This is reflected in the company’s emphasis on the personal value component of the CHSP as well as in the recognition programs developed to reinforce a strong safety culture. Both are clear signals to employees that safety is vital to the organization and not just lip service.

For its 100,000 drivers, UPS recognizes safe driving milestones in five-year increments. It also has a program called the Circle of Honor that recognizes any driver who attains 25 years without an avoidable accident. UPS’s senior most-safe driver, who has gone 49 years without an avoidable accident, was featured in a 30-minute television program called, appropriately enough, “American Trucker.” UPS has 5,428 active drivers with 25 years or more of safe driving. The company also recognizes part-time employees for working safely. It is not uncommon to have work groups achieve over 100,000 safe work days.

Each UPS facility is encouraged to develop its own recognition program, and CHSP committees are trained on how to effectively utilize rewards and recognition. This training teaches them the difference between different tiers of rewards. Tier I rewards focus on individuals and their behaviors. For example, individuals that minimize at-risk behaviors such as bending at the knees (not at the waist), or using their “power zone” by keeping the package between their knees and shoulders and close to the body are praised for their efforts.

Tier II awards emphasize group accomplishments. For example, driver groups that go a whole week without an accident are given a cookout or put in a raffle for a pair of driver socks. Tier III awards recognize facility successes such as an entire building going for a length of time, say 10,000 days without an injury. Such a performance is rewarded with cookouts and breakfast cooked by the management team. This tiered approach allows CHSP committees to drive the recognition process, making it meaningful for all employees.

2. Process stages and work methods must be formally outlined. UPS views itself as an engineering company that happens to deliver packages. That engineering mindset recognizes the need to formalize work methods and process activities, outlining all steps and stages so as to gain a more complete understanding of everything that the process encompasses. By understanding all the intricacies of every task that is performed, a company is better equipped to know where unsafe activities can potentially occur.

3. Training (and re-training) on the methods sets the stage for safe actions. Once a system has been formally defined, training mechanisms need to be developed, communicated, and made routine. UPS understands that continuously making employees aware of the keys to working safely is a central component of a good safety process. This heightened sense of awareness keeps safety in the forefront of an individual’s thinking while making safe work habits the default method in times of stress.

4. Performance measurement is essential. A comprehensive safety program requires that all employees act toward a common mission. Importantly, measures must be in place to gauge their progress against that mission. In general, measurements need to be suited to the specific environment. But the real key is that metrics reflect the goals of the processes as well as the manner in which individuals are trained. From such measurements, a company will be able to evaluate its progress toward meeting the goal of a safer workplace.

5. Analysis should focus on root causes. The assessment of safety should not stop at the measurements themselves. It also needs to look to the reasons behind the numbers. The key is to delve deeply into the analysis in order to determine the root causes of accidents, injuries, or even unsafe behaviors. Understanding the cause leads to better solutions that, in turn, lead to improved performance.

6. Giving the system to the people is the ultimate key to continued safe operation. An effective safety process relies on the individuals working within the context of the operating environment. Empowerment in its truest sense is practiced by entrusting frontline hourly workers, drivers, and package handlers, with the responsibility for safety. This represents an evolvement from a system that was driven totally by management to a system wherein the employees drove safety initiatives. By giving more control to frontline people, UPS changed an engulfed culture of managerial-driven actions that had been in place for almost 90 years.

Implications for Supply Chain Management

The UPS case study has broader implications for multiple facets of supply chain management. And as with the lessons learned, these implications extend to companies across business sectors.

First and foremost, there is the need to incorporate the safety provision in all process designs. This holds true for any business—from manufacturing companies to restaurants and hospitals—where people are integral parts of the system. Specifically, safety aspects must be designed in the process at every level of activity, from the task level to the overall operating level of a facility. For instance, while designing the layout of distribution centers, proper measures for adequate lighting, heating and cooling, aisle spaces, and ergonomic work design must be considered. Because of the long-term nature of process design decisions, non-optimal choices will be hard to change in the near term and can prove to be very expensive over the long term.

Second, the implications for supply chain design stem from the in-depth process analysis that is undertaken to understand how product design and process design are interconnected. More specifically, improper product and/or process design features could contribute to the occurrence of accidents and injuries. Over and above the gains from fewer accidents and injuries, UPS was able to build a leaner supply chain by using a combination of lean and Six Sigma tools and the scientific method. In fact, this expertise was developed to such an extent that the company offers supply chain consulting to small and medium enterprises in the area of inventory management and supply chain redesign.

Third, with respect to fleet design, the recent emphasis on carbon footprints and energy costs has put tremendous pressure on companies to think innovatively about cutting energy costs and reducing consumption of non-renewable energy sources. When diesel costs started to increase sharply, UPS came up with a GIS-based planning system that monitored idle times of the fleet. This led to an innovative solution for improving fuel efficiency: Reduce the number left turns taken by drivers. As another example, UPS in its distribution centers uses battery-operated material handling trucks that can be recharged at the distribution center for a longer, more efficient operating life cycle.

Fourth, the UPS case study has important implications for talent development of people involved in the safety efforts. By giving employees ownership in the safety process and encouraging creativity, UPS benefitted from lower injury rates, more productive employees and facilities, and more satisfied workers who experienced a sense of pride and fulfillment from their job environment. It is interesting to note that at UPS almost everyone starts part-time. Individuals then apply for the full-time driver slots once they have proven themselves in the sorting ranks (not unlike an apprenticeship system).

UPS prides itself on its promotion from within policy. It has learned through the decades that managers who have a deep understanding of the business are the best candidates to transition into staff functions like Health and Safety. That’s why nearly every safety manager in the UPS network has come from within the company’s operational setting.

Fifth, the UPS story has implications for training needs. UPS invests in an intensive, on-the-job training regimen that teaches employees the fundamentals of the company’s Health and Safety system. New safety managers also attend “Safety 101” workshops for one week at corporate headquarters. This ensures consistent adherence to regulatory constraints and internal processes.

There is a heavy emphasis on operational training as well. Tractor-trailer drivers receive 40 hours of training, comprised of 40 hours in the classroom training and 40 hours on the road. Delivery drivers undergo an intensive six-day training program. Training and testing is taken seriously. In fact, employees can be demoted from driving back to the sorting ranks if they fall behind on their safety training and performance.

Finally, the UPS case study has implications for supply chain-wide communications with stakeholders. The successful implementation of the safety process at one site is diffused to other sites and shared through the company’s intranet-based tool on health, safety, and wellness. In addition, UPS regularly communicates its successes with the safety initiatives to external customers.

All in all, the UPS story is a comprehensive illustration of excellence in safety across multiple dimensions. And through its pursuit of superior metrics, the company continues to raise the bar. Indeed, UPS has set the stage for other companies to follow suit while providing some valuable lessons learned to help them in that endeavor.

End notes:

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) 2011.

Jayaram, J. Das, A., and Nicolae, M., 2010. “Looking Beyond the Obvious: The Synergistic Benefits of the Principles underlying Toyota Production Systems,” International Journal of Production Economics, 128(1), 280-291.

About the Authors: Dr. Jayanth Jayaram is Full Professor of Management Science and Moore Research Fellow at the University of South Carolina. Dr. Jeff Smith is Assistant Professor of Operations at Florida State University. Sung-Hee “Sunny” Park is Assistant Professor of Management Information Systems at Dalton State College. Dan McMackin is a Public Relations Manager for UPS. The authors can be reached through [email protected].