A Practitioner’s Guide to Demand Planning

Effective demand planning doesn’t just happen, it requires work. To move forward, companies have to admit the mistakes of the past, implement continuous improvement programs to drive discipline, and carefully re-implement demand planning technologies.

Within most organizations, the words “demand planning” cause a reaction—and typically not a mild one. It is characterized by emotional extremes like anger, despair, disillusionment, or even hopelessness.

Seldom do we find a team excited or optimistic about their chances to improve demand planning processes.

After two decades of process and technology refinement, excellence in demand management still eludes supply chain teams. In fact, it is the supply chain planning application with the greatest gap between performance and satisfaction. At the same time, it’s the application with the greatest planned future spending.

For most teams, demand planning is a conundrum, a true love-hate relationship. They want to improve the demand planning process, but remain skeptical that they can ever do so.

In our research at Supply Chain Insights, we find that demand planning is the most misunderstood—and most frustrating—of any supply chain planning application. While companies are the most satisfied with warehouse and transportation management, they are the least satisfied with demand planning.

Teams are also confused about the demand planning process. They are unclear on how to move forward. What drives process excellence is not clear. And well-intentioned consultants brought in to help achieve that clarity often give bad advice.

In this article, we share insights on the current state of demand planning and give actionable advice that supply chain teams can implement to make real improvements.

Getting Past the Plateau

The first use of the term supply chain management in the commercial sector was in 1982. Until that time, the focus of organizational improvement was on specific functional areas such as manufacturing, procurement, or logistics.

This “siloed” approach gradually gave way to more integrated operations, which lead to the concepts of demand planning and integrated supply chain planning.

In this article, demand planning is defined as the use of analytics—optimization, text mining, and collaborative workflow—to use market signals (channel sales, customer orders, customer shipments, or market indicators) to predict future demand patterns.

This forward period for demand planning will vary by company, but it is a tactical planning process typically stretching across the period of 10 months to 18 months.

Note that as companies mature, the use of the forecast becomes more comprehensive and is woven into a number of processes culminating in a more holistic end-to-end process termed demand management. (We discuss this more fully in the article “Concepts of Demand Management”)

The first demand planning applications were introduced late in the 1980s. Today, there is a conventional view that as these applications evolved, companies have steadily reduced costs, improved inventories, and sped time to market.

The actual balance sheet results, however, show the opposite. Too few supply chain teams have successfully posted improvements to their balance sheets through demand planning initiatives.

Improvements were made in specific projects and in isolated parts of the business, but progress has slowed over the last 10 years resulting in a supply chain plateau. Growth has been slowing, inventories climbing, and costs escalating.

Getting the basics right in the demand planning process is essential to moving supply chain results past the current plateau. However, too few companies know what to do or how to do it.

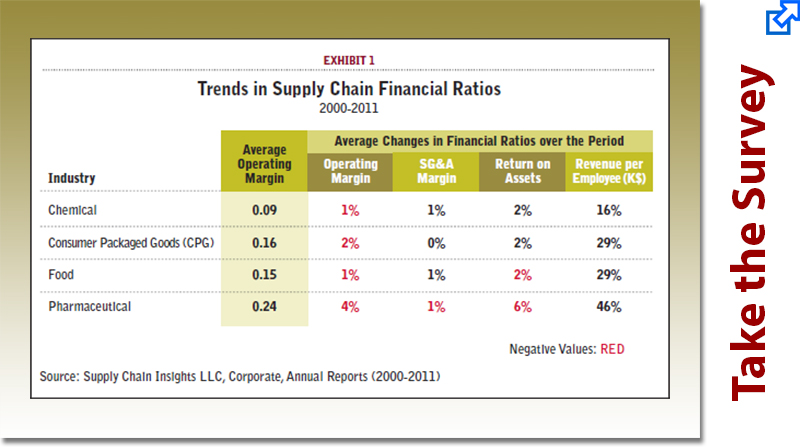

Evidence of this plateau is shown in Exhibit 1. In the process manufacturing sectors shown, where demand planning should make a dramatic difference, companies are going backward not forward in driving meaningful results. Ironically, most companies do not realize that they have reached a supply chain plateau because they have not looked at year-over-year financial balance sheet results.

Take the Supply & Demand Planning Software Survey

For your participation in this survey, Lora Cecere, Supply Chain Insights Founder & CEO, will provide a free one hour consultative call with you and your organization to review the results and discuss your own talent strategies.

Take Your Supply and Demand Planning Software Survey

The supply chain is a complex system that has grown even more complex over the decade. Most companies understand that it is complex, but they do not see it as a complex system. In a complex system there are finite trade-offs between areas. In the supply chain, these trade-offs include growth, costs, cycles, and complexity.

Each supply chain has a unique potential based on the trade-offs of these factors. As a result, companies cannot make improvements in operating margin without affecting inventories unless they improve the supply chain potential. One of the most effective ways to increase the potential of the supply chain is to improve the demand signal.

The challenge of getting past this plateau is as important as it is formidable. Supply chains are becoming more complex. As products proliferate, channels become more specialized and as companies span global geographies, demand planning principles grow in importance.

Organizational design, process design, and how the data is used in demand processes all play a major role in defining the differences between leaders and laggards.

An important factor in making demand planning progress is the design of reporting relationships. Based on our work with more than 300 companies, we have concluded that a reporting relationship to a central group or a supply chain center of excellence gives companies an advantage in getting past the plateau.

By contrast, companies with reporting relationships to the sales organization tend to post the worst results in demand planning. These organizations are plagued by high, and often uncontrolled, bias.

Reporting relationships to marketing and manufacturing are similarly problematic. The bias in these relationships is not as high as it is with sales reporting, but it is higher than in organizations with reporting relationships to a neutral, cross-functional analytics group.

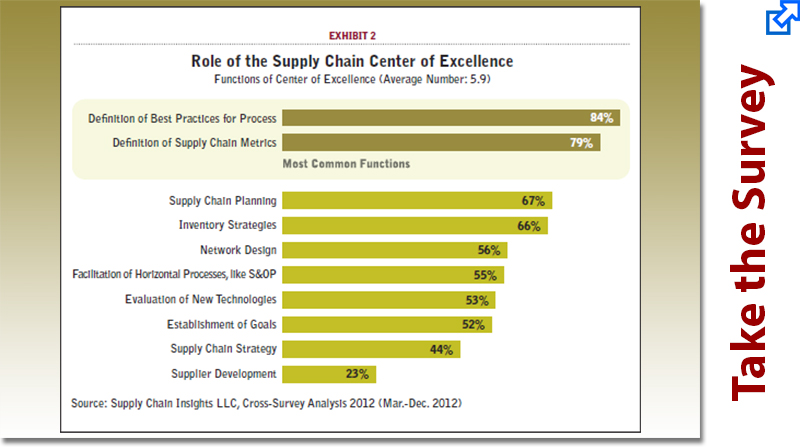

Our research shows that 64 percent of companies today have a supply chain center of excellence. As shown in Exhibit 2, these teams take responsibility for global planning and global/regional governance of demand insights and data integrity for the organization.

Data governance in design of the global supply chain is another key success factor. Often there are demand teams in the dispersed regions sending market signals into the plan and global teams at corporate that are gathering information on global programs.

Both are important, but they need to know how to work together. This does not happen by chance; it requires clear and careful design. Corporate organizational design needs to carefully architect the relationships between global planning and regional execution.

While form should follow function, a clear understanding of supply chain basics is essential. Too often, companies overlook this important design element of demand data governance and the roles of regional/global governance.

Demand Volatility: A Rising Concern

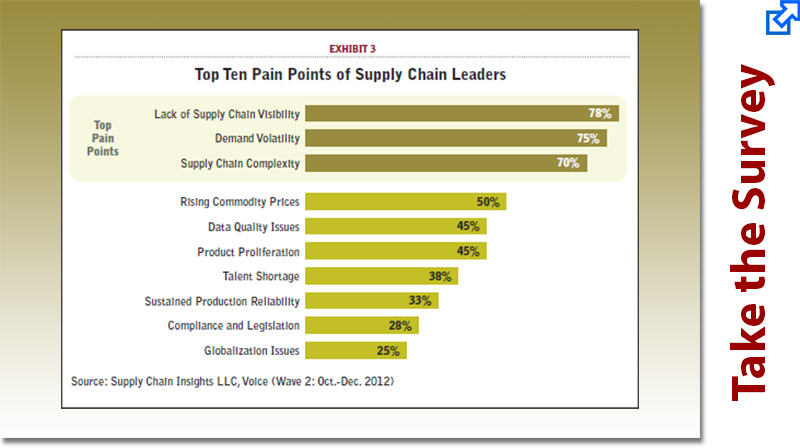

As shown in Exhibit 3 (top 10 pain points shown), supply chain leaders are becoming increasingly concerned over demand volatility. Global market expansion and specific regional needs heightens this concern.

Further, the proliferation of products and the changing needs of customers make it more critical than ever to sense market demand and quickly translate the requirements into the supply chain response.

The “forecastability” (ability to use optimization techniques to improve forecast accuracy numbers) of products is getting more difficult. Demand volatility is growing, demand data is becoming more complex, and the usual responses are less effective.

The traditional supply chain design is unable to sense and adapt to rising demand volatility. Demand management systems were designed to optimize demand signals periodically (weekly or monthly) from order or shipment data.

Order data, by definition, carries latency. This latency can be substantial - from one week to five weeks - based on the time that it takes to roll up channel pull into minimal order quantities across the channel.

In short, the traditional supply chain is designed to respond - not to sense. As market opportunities change, this design cannot flex and adapt; the companies are not well-suited for periods of high demand volatility.

Creating an adaptable system that can sense and respond - and better manage volatility - requires a radical departure from traditional design approaches. The system needs to be designed from the outside-in. It needs to embrace the concepts of demand management.

This includes sensing channel demand; using optimization to actively shape demand; and applying advanced analytics used to drive an intelligent response. At a foundational level, demand planning, and the reduction of bias and error, is important. This is a radical departure from the design approach of the last decade.

So, how do companies get started? How do they overcome the challenges? Based on our experience working with a range of companies, we believe that it is a three-step process.

Step 1: Face the Mistakes Made in the Past

The first step in combating demand volatility is to admit the mistakes of the past. The problems associated with faulty technology implementations are compounded by the adoption of bad practices.

In this journey to sense and shape and use demand information to drive a more profitable response, leaders need to confront mistakes made in the design and adoption of demand processes over the course of the last decade. The most important of these mistakes include the following:

One-number forecasting. Well-intentioned consultants tout the concept of one-number forecasting. Eager executives drink the magic elixir. Problem is, they realize all too late that the one-number mantra actually increases—not decreases—forecast error. The reason: It’s too simplistic, something the one-number advocates fail to understand.

A demand plan is hierarchical around products, time, geographies, channels, and attributes. It is a complex set of role-based, time-phased data. Within this context, a one-number thought process is naive.

An effective demand plan has many numbers that are tied together in an effective data model for role-based planning (that is, based on defined roles across the organization including sales, marketing, and supply chain) and what-if analysis.

A one-number plan is too constraining for the organization. So instead of one number, the focus needs to be a common plan with marketing, sales, financial, and supply chain views and agreement on market assumptions.

Achieving this level of agreement requires the use of an advanced forecasting technology and the design of the system to deliver role-based views. This can only be found in the more advanced forecasting systems.

Consensus planning. Over the last 10 years, the concept of consensus planning has taken hold in many organizations. It’s based on the belief that each organization within the company can add insight to make the demand plan better. The concept is correct; but in most instances, the implementation has been flawed.

The issue is that most companies did not hold groups within the organization accountable for bias and error. Each group has its own natural bias and error based on incentives. So unless there is discipline around the incentive structure, consensus forecasting will distort the forecast and add error despite well-intended efforts to improve the demand planning process.

Forecasting what to make vs. the channel demands. The traditional technique is to forecast what manufacturing should make as opposed to forecasting what is selling in the channel. Contrary to what many think, this is not a trivial difference.

Forecasting channel demand reduces demand latency and gives the organization a more current signal. It also allows for augmenting the forecast with demand insights to improve forecast quality. For most companies, this requires a reconfiguration of the demand planning software.

Rewarding the urgent vs. the important. Time after time, we see companies implement demand planning technologies and improve forecasting processes, but not improve their supply chain results. The issue is the lack of training on how to “use the better forecast signal.” Most supply chain teams do not know how to use the forecast effectively.

Instead of trying to correct inaccurate data and focus on a finite number, the teams need to use the probability of demand in their network design and supply planning models. This takes training.

The adoption of CPFR: Collaborative Planning Forecasting and Replenishment, or CPFR, saw its greatest adoption in the consumer packaged goods industry.

The idea was for manufacturers to collaborate with their retail partners on the building of a demand plan for the extended network. CPFR was designed to align the manufacturer’s demand plan to the retailer’s and reduce the bullwhip effect.

The assumption was that the retailer’s forecast would provide better insights. The problem, however, was that the maturity of the retailer forecast was never considered. The reality is that most retailers have poor forecasts, and the CPFR process never accounted for the inherent bias and error in their forecasts.

There’s really only one retailer that measures forecast accuracy and accounts for bias and error: Walmart.

Step 2: Buy the Right Demand Planning System

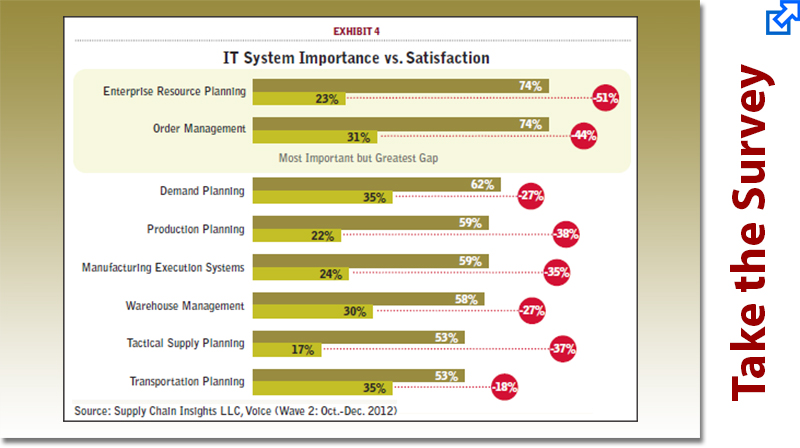

Our research shows that demand planning, ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning), and order management rate as the most important supply chain technologies to supply chain leaders.

However, these areas also show wide gaps between system importance and current level of satisfaction (see Exhibit 4). Ironically, they are the technologies with the greatest planned spending, too. Of all of the supply chain planning applications, success in demand planning remains the most elusive.

And despite the evolution of technology capabilities for in-memory processing, cloud-based analytics, and deeper optimization, very little has changed in most demand planning applications.

Consultants will often defer to the ERP system demand planning technology in helping companies with the selection processes, using the rationale that “80 percent fit of the solution is sufficient.” But in reality this is the exception, not the rule.

Unfortunately, most consultants have a limited view of what is available and are incented to implement the “most expensive” vs. the “best” solutions. As a result, the technologies with the best data model fit are seldom considered because they are less-expensive than best-of-breed solutions.

To ensure that you select the right technology for your operation, it is critical to map the demand streams and the demand drivers. Features like causality, seasonality, tops-down and bottoms-up forecasting, and forecast-value add analysis are essential to the selection of the technology.

Step 3: Carefully Implement

So how do we move forward and close the gap? It starts with the implementation. Companies that are the most successful in demand planning tune the optimization engines through a series of conference room pilots to drive the highest forecast accuracy.

The goal here is not to accelerate the speed of project implementation. Instead, it should be to drive the best results by focusing on the following:

A well-designed pilot. To implement the demand management system correctly, take two years to three years of shipment, order, and channel data and use the historic data to forecast a known outcome of the latest year.

(For example, tune a model using 2009, 2010, and 2011 data to forecast actual output in 2012. Keep fine tuning the model to close the gap between the predicted and actual results for 2012.) To fine-tune the models, divide the data into demand streams and work each demand flow for refinement.

Examples include slow-moving seasonal items, fast-moving turn volume products, new product introductions, special packaging items, and special promotions.

The best demand planning implementations take time. The foundation of this effort is a carefully crafted pilot to identify the right market drivers and test the optimization engines.

Many companies make the mistake of rushing the demand planning implementation and not aligning the technologies to get the best results.

Regular tune-ups. Just as a car requires frequent tune-ups, so does the demand planning implementation. This is not a technology implementation project that can be installed and then forgotten.

The most successful companies achieve superior results through yearly tune-ups. These include the cleansing of data, the alignment of planning master data, and the fine-tuning of demand optimization engines.

A demand planning team. Another stumbling block centers on the training of the teams that maintain the demand planning systems. A frequent mistake is to staff the demand planning team with junior analysts and use the assignment as a stepping stone for greater accountability.

The companies with the greatest success with demand planning implementations staff the group with senior people that know the business. Further, they reward the team members with progressive assignments for their work. For the great majority of demand planning positions, internal training will be required.

There are not enough trained professionals in this field available for the number of open positions. This is a critical talent management challenge.

A mindset change. Many supply chain professionals have given up hope that they will ever be able to improve the demand forecast. They have witnessed project after project to reduce forecast error and improve inventory accuracy with no results.

But progress can, in fact, be made, by carefully articulating the path forward to drive continuous improvement in the demand planning process and by working with supply chain teams on how to better use the forecast.

Time after time, we see companies improve their forecast, but fail to teach the supply chain team how to use the improved forecast. Effecting the needed mindset change is basically a matter of education.

Bias and error reduction. The use of forecast value-add (FVA) analysis helps companies add discipline to the demand management process to drive continuous improvement.

This is best described by Mike Gilliland in his book The Business Forecasting Deal: Exposing Myths, Eliminating Bad Practices, Providing Practical Solutions (Wiley and SAS Business Series). Through the use of FVA, the steps to develop the demand plan are carefully examined to understand if the process is improving or degrading the forecast.

Process redesign. To reduce demand volatility, design the process outside-in from the channel back. Focus on sensing what is being sold in the channel. This is a radical departure from the traditional manufacturing process of forecasting what a company needs to manufacture.

The key steps of this design approach are:

- Map all of the demand signals outside-in: Start by mapping the demand signals outside-in from the channel back. In the conference room pilot, validate which market signals are critical and useful for modeling. Focus first on market data, and then on the clean-up of enterprise data.

- Build the data model based on channel inputs from the channel back: After mapping the market signals, build a demand model to forecast the channel. Focus on modeling the “ship-to” locations. Reduce demand latency to sense market variations by building strong demand translation capabilities.

- Don’t try to get perfect on imperfect data. While many companies focus on getting very specific on demand numbers, focus instead on the probability of demand and the understanding of demand patterns. Put another way, “learn how to dance with gray.”

The Keys to Moving Forward

The world of demand planning has changed. The business requirements have escalated and it matters more than ever. To move forward, companies have to admit the mistakes of the past, implement continuous improvement programs to drive discipline, and carefully re-implement demand planning technologies to sense and shape demand.

The evolution to demand excellence needs to be built on a program of continuous improvement focused on forecast-value added techniques to reduce bias and error. Effective demand planning doesn’t just happen, it requires work. It is contingent on the ability to build the right teams, and bring a new level of excitement and open mindedness to driving a demand signal.

Those that do it best are comfortable dancing in the world of gray where each day offers a new opportunity and where demand holds value.

About the Author

Lora Cecere is the Founder and CEO of Supply Chain Insights , the research firm that’s paving new directions in building thought-leading supply chain research. She is also the author of the enterprise software blog Supply Chain Shaman. The blog focuses on the use of enterprise applications to drive supply chain excellence. Her book, Bricks Matter, published in December of 2012.