5 Lessons for Supply Chains from the Financial Crisis

For many supply chain executives, the Financial Crisis has been one of the toughest challenges in their careers. Firms across industries were required to deal with huge demand-supply mismatches caused by collapsing demand.

Firms have always been challenged to adapt their supply chains to their success in the market.

During boom periods, firms are eager to avoid costly backlogs, to align manufacturing capacities with growing demand, and to ensure raw materials from new suppliers.

Meanwhile, supply chains are accelerated, costly air freight is accepted, and large batches are produced because goods will be sold at some stage. In contrast, during difficult times, firms must address shrinking customer orders, face increasing competition, and see decreasing margins.

Accordingly, priorities for supply chains differ significantly. Firms must focus on cutting costs, reducing capacities, consolidating suppliers, and freeing up cash by taking out inventory.

Difficult times frequently relate to an individual firm’s situation: These could include poor top management decisions, cost pressures from a new competitor, or demand being hit by poor customer service. However, difficult times are also frequently caused by changing economic climates.

During the Financial Crisis that started five years ago, an unforeseen contraction in demand across numerous industries challenged supply chains globally beyond anything observed in the past. As the economy continued to drift downward, a significant turning point occurred on September 15, 2008, when Lehman Brothers, the fourth largest U.S. investment bank at that time, declared bankruptcy. The collapse of Lehman Brothers sent a shockwave through the financial world and triggered an unprecedented decline in the global economy.

In particular, the manufacturing sector suffered severe consequences as a result of the recession: Industries such as machinery, metals, and transportation equipment observed drops in customer orders by up to 42 percent within a single year (see Exhibit 1).

Many companies struggled to survive and entire supply chains were threatened with collapse.

Those firms that survived the Financial Crisis reacted swiftly and decisively. Often, they leveraged innovative approaches to safeguard their internal and external supply chains amid the challenging business climate.

Today, many firms continue to deal with individual challenges. Similarly, the economic situation in many parts of the world has become unstable. For those reasons, innovative approaches for managing supply chains in a downturn could become as important now as they were just five years ago. Based on a series of interviews with executives from numerous firms affected in the Financial Crisis, we identified five action areas supply chain executives should be familiar with.

Supply Chain Actions in Difficult Times

Management actions in difficult times are well known and are typically in line with classic turnaround approaches. These actions include engaging in significant cost reduction (including overhead costs), introducing zero-based budgets, establishing war rooms, and redefining footprints and networks. However, it is also crucial to understand the trade-offs between myopic and sustainable actions. In addition, it is key to plan for the inevitable and prepare the supply chain to deal with tough times.

For example, when a mid-sized third tier automotive supplier in Southern Germany was confronted with significant demand reductions, the company reacted quickly. The supplier closed one production site, shifted production volumes to low-cost countries, and furloughed employees to adjust to the decrease in volume. Unfortunately, the specific knowledge that was required to establish new production lines was not transferred.

Moreover, the company went through a lean manufacturing program, setting inventory holding cost at a high level of 40 percent, which was excessive for its low to medium value-dense products. Although all of the crisis measures were appropriate, applying the measures in parallel placed the company under severe pressure, causing the firm to deplete its cash stores near to the point of bankruptcy.

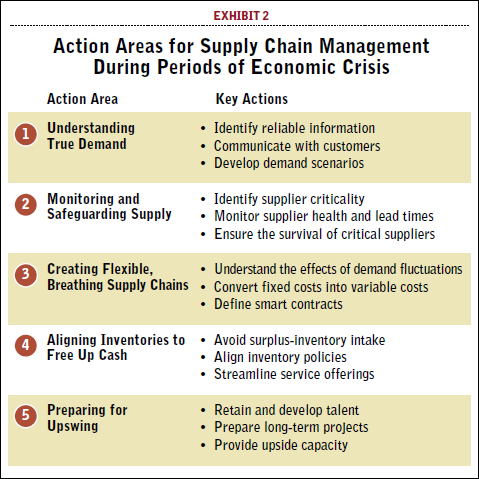

In a supply chain context, the five action areas that are illustrated in Exhibit 2 are essential to cope with any type of crisis situation—individual as well as economic.

First, supply chain managers should gain a clear understanding of potential demand scenarios, as demand should be the basis of all supply chain planning.

Second, firms should safeguard their supplies to avoid any critical bottlenecks as suppliers go out of business.

Third, firms must accelerate all efforts to create flexible and breathing supply chains that can cope with all types of variability.

Fourth, managers should carefully reduce inventories to free up cash that is essential for turnaround actions. Finally, firms should also consider the light at the end of the tunnel and should begin to position themselves for the inevitable upswing.

Based on our experience, all five action areas must be considered in parallel, which will cause exceptional challenges for supply chain managers while also dealing with all types of operational glitches. Accordingly, we believe that firms should begin to prepare as early as possible for difficult times ahead. In the end, they will not only benefit in the crisis but actions are also beneficial to the business from a long-term perspective.

Understanding True Demand

One key lesson from the Financial Crisis was that numerous firms underestimated the severity of the declines in demand, which reached 90 percent in some firms. Because forecasting demand is the starting point of all planning (i.e., capacity planning, supply planning, and production planning), it is crucial to understand true demand. Indeed, any significant over- or under-reaction could trigger a disaster. Accordingly, successful companies have pursued three key actions to improve their understanding of demand: (i) identifying reliable demand information, (ii) communicating with customers, and (iii) developing demand scenarios.

Identify reliable demand information. For most firms, the visibility of true customer demand was close to zero at the beginning of the crisis. Many found it challenging to identify reliable demand information. In addition to high levels of economic uncertainty, opportunistic competitor actions to fill capacities induced additional uncertainty. Even long-standing orders were subject to cancellation as a result of collapsing customer demand. For example, a Scandinavian heavy equipment manufacturer lost nearly all previously booked orders from Russia because of limited credit availability of these customers.

For this reason, successful firms establish a process to monitor the probability of order cancellations that is similar to the processes for monitoring the probability for winning orders. Frequently, companies began to realize that leveraging information from the over-opportunistic sales force did not provide any transparency, as sales personnel were still handcuffed to their budget thinking. When challenged to explain their sales forecasts, personnel often expressed concerns that capacity could be reduced too sharply and that longer lead times would alienate customers. Successful firms rapidly moved away from initial budgets and targets by implementing a new zero-based budgeting process.

Communicate frequently with customers. Numerous companies also established more frequent communication with customers and placed more emphasis on short-term forecasts. When the symptoms of recession began to emerge, one automotive supplier reduced the firm’s forecast horizon, and sales personnel increased chatter with customers. However, communication through established channels between sales and procurement departments often did not provide sufficient visibility, as the information flow was slow within the customer organization.

Procurement departments themselves frequently had no visibility regarding procurement volumes in the upcoming weeks and months. Accordingly, increased direct communication began to occur among planning departments while contract details were coordinated between sales and procurement departments. Some companies also began to further integrate planning systems and established EDI to obtain real-time updates on planned volumes.

Another example of effective communication is a vertically integrated chemical company based in Germany that produces goods for all stages of the chemical value chain. By sharing demand information on all types of fine and base chemicals internally, managers established a reasonable picture of the market demand for different products several months in advance.

Prepare multiple demand scenarios. Because of limited visibility, a single forecast for a product line was often difficult to obtain. Therefore, successful companies began to prepare multiple demand scenarios and to plan their actions within these scenarios. Such scenarios included consideration of the following questions:

- Is the worst case that demand decreases by more than 80 percent?

- What is the outcome if all of our customers in France close their plants for three months?

- What are the aggregated inventories of all European customers, and would these customers need to divest all of their stocks?

- How long can we employ our workers given the current order book and the lack of new demand?

Top companies have endeavored to answer these types of questions and have typically aggregated them into a few scenarios. Several companies have even developed more advanced economic models to analyze the effects of early indicators on the world economy and to develop scenarios and action steps accordingly.

Monitoring and Safeguarding Supply

The suddenness and severity of the recession forced many firms to the brink of bankruptcy. While sales and demand reached all-time lows, sourcing departments faced an entirely new challenge—the risk of losing suppliers and entire supply chains due to bankruptcy.

Accordingly, successful firms exerted significant efforts to safeguard their supply. Typically, they implemented an advanced supplier risk management system that included three actions: (i) identifying supplier criticality; (ii) monitoring supplier health and lead times; and (iii) ensuring the survival of critical suppliers.

Identify supplier criticality. Although most firms have established a regular risk assessment and management process, these processes typically focus on physical supply chain disruptions such as natural disasters or strikes. The risk of losing suppliers next door is often neglected. Therefore, supplier criticality needed to be reevaluated based on the risk of supplier insolvency. Which critical parts and how much volume do we obtain from a supplier? Which alternative suppliers are certified? What volumes can these alternative suppliers provide? Who owns the tools and forms?

Often, second-tier suppliers and subcontractors also contributed to the problem, particularly in the automotive industry. For this reason, firms that had prepared supply chain mapping scenarios could now more easily identify the potential effects of supplier defaults.

Monitor supplier health and lead times. Once supplier criticality was identified, firms were required to monitor supplier health and lead times. To monitor supplier health, successful firms leveraged all types of internal and external sources, such as buyers’ information on the speed at which suppliers were committing to orders or requesting earlier payments, information from plant visits regarding utilization, and newspaper/industry discussions on sell-and-lease-back deals or the loss of key people to understand the “real” situation of the supplier.

Additionally, many firms carefully reviewed the quarterly financial statements of their suppliers. In any scenario, the monitoring of suppliers must be carefully coordinated, including the identification of lead persons who collect all information.

In addition to supplier health, successful firms also carefully reviewed supplier lead times. Low order intake often had an inverse effect on lead times because suppliers reduced their capacities to stretch their order books over longer periods. Therefore, firms needed to proactively align with suppliers with respect to new delivery schedules.

Ensure the survival of critical suppliers. Communicating frequently with suppliers and being a “good” customer is often beneficial for firms during more comfortable financial times. Paying invoices on time rather than stretching payment terms can ensure a preferred customer rating that allows additional favors in the future. Nevertheless, several companies have been forced to ensure the survival of critical suppliers. In instances where no alternative suppliers for critical goods were (yet) available, firms supported suppliers by pooling spending or taking inventory ownership from suppliers to ease their financial burdens.

Particularly in small oligopoly supply markets, firms have tended to prefer supporting a struggling supplier rather than coping with an even more concentrated supply base in the future. In extreme cases, firms also attempted to actively reshape their supply base according to their strategic objectives. For example, one automotive OEM defined its preferred supplier landscape for a certain category and actively reallocated sourcing spending to the preferred suppliers, thereby destabilizing out-of-favor suppliers and rendering them easy acquisition targets.

Creating Flexible, Breathing Supply Chains

When demand plunged in the Financial Crisis, numerous firms grappled with overcapacity and struggled to right-size their operations in the short term. These challenges were often inevitable because network design and footprint decisions had been carefully planned and implemented over the course of several years for a very specific demand scenario.

For the future, we suggest managers proactively address demand uncertainty and create supply chains that are flexible to a wider range of demand. We use the term breathing supply chains for setups that can efficiently provide output at different quantities. Breathing supply chains are also a means to deal with fluctuations in more regular operations. We find that successful companies pursued three key actions to implement them: (i) understanding the effects of demand fluctuations; (ii) converting fixed costs into variable costs; and (iii) defining smart contracts.

Understand effects of demand fluctuation. One key task in defining supply chains is to match capacity with demand. Accordingly, it is crucial to obtain a fair understanding of the effects of demand fluctuations. Firms must identify which actions should be selected based on the prepared demand scenarios and must embed the breathing supply chain thinking into their supply chain strategies by asking questions such as: How do we provide the most flexibility regarding any changes in demand?

For each demand scenario, a firm must identify preferable actions that holistically consider the effects of selling, closing, or idling manufacturing assets as well as any potential insourcing or outsourcing effects. On a more operational basis, situations are frequently complicated by increased MRP complexity in low-demand situations as a result of coupled production, minimum batch sizes, and order quantities.

Convert fixed costs into variable costs. Ultimately, it is crucial to convert fixed costs into variable costs to compensate for lower production levels by diminishing marginal costs. Firms have often closed or idled assets with lower productivity while carefully considering the incremental costs of moving production to other plants. One alternative for reducing fixed costs involves increasing the utilization of “fixed” assets and labor by insourcing.

Whereas outsourcing has become a common practice for addressing bottlenecks and reducing costs in normal economic conditions, many firms have focused on insourcing during the Financial Crisis. For example, for firms in the machinery sector, insourcing standard manufacturing processes, such as milling, welding, or assembly operations, appears to be rather simple. Through insourcing, firms were able to increase worker and asset utilization even when internal productivity was lower. However, firms must minimize insourcing costs by cross-training workers, maintaining the required tools, and developing smart contracts that avoid penalties.

Define smart contracts. The definition of smart contracts with suppliers plays a crucial role in creating breathing supply chains. Many firms closed long-term contracts with suppliers to benefit from discounts. However, once locked in, volume or price reductions often depend entirely on the good will of suppliers. Successful companies have considered fluctuations in demand when defining their contracts. For example, one Dutch chemical company had an annual contract with a provider of tank capacity beginning on January 1. The firm received a volume discount based on the tank capacity signed for the year.

However, company officials realized that the firm would need to pay for unused tanks or would fail to receive volume discounts if capacity requirements deviated from the plan in mid-year. Therefore, the firm opted for a smart contract design. Rather than renting all tank capacity on January 1, the firm now begins its annual rents on a rolling basis throughout the year (e.g., certain capacity on January 1, certain capacity on February 1). Rather than receiving a volume discount on the capacity signed at the same time, the discount is now based on the capacity rented at a given time. The firm can easily discontinue the rent for the tank with the next expiring contract to adjust capacity while continuing to receive high-volume discounts for the remaining tanks rented. The example highlights the importance of considering your options before any crisis arises to ensure flexibility in tough times.

Aligning Inventories to Free up Cash

Reducing inventories while meeting service-level requirements has always been a key challenge for supply chain managers. However, the limited availability of credit during the Financial Crisis triggered a skyrocketing interest in optimizing inventories, as firms were required to free up significant amounts of cash on short notice. The situation became even more challenging as a result of unfavorable inventory dynamics.

A significant reduction in sales slowed the outflow of goods to customers; customers were consuming their usual inventories at a lower rate and additionally reduced their safety stock levels to a lower level, thus triggering a multiplier effect.

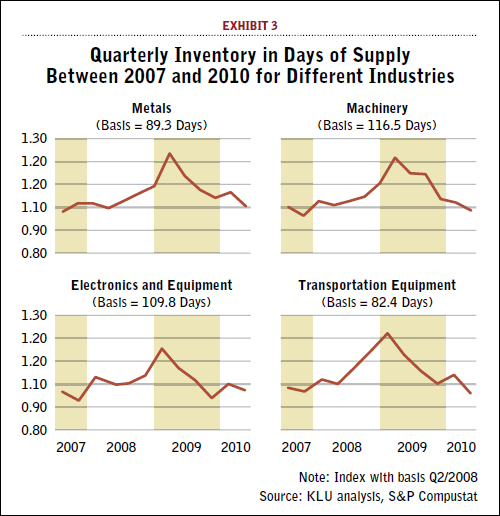

Accordingly, supplier production plummeted, and firms could only gradually consume their raw material stocks. As a result, many firms observed the characteristic inventory hump (see Exhibit 3). Inventories hit the roof across industries in 2009 and increased by up to 70 percent within six months until the trajectory reversed.

Our interviews with successful inventory managers highlight three practices that enabled managers to avoid or at least to balance the inventory hump: (i) avoiding surplus inventory intake; (ii) aligning inventory policies; and (iii) managing service offerings.

Avoid surplus inventory intake. Although inventory managers have few options to increase the sales that trigger the outflow of goods, it is essential to halt the inflow of surplus goods that will require a long time to turn. We found that successful firms reacted firmly to the decrease in demand and implemented a moratorium on material orders to avoid any intake of surplus goods. Similar to a travel ban, firms reviewed all material orders against their demand scenarios and scrutinized their supplier contracts for cancellation opportunities. Even if contracts did not allow for order cancellations, firms often successfully negotiated with suppliers to extend volume commitments over longer periods of time. Several companies also managed to sell raw materials to other manufacturers that in turn benefited from favorable prices.

Align inventory policies. The significant change in demand required numerous firms to review and align their inventory policies. Frequently, order quantities were reviewed and reduced. For example, one leading European automotive supplier changed the typical order size for a certain category from full truckload to half truckload in an effort to minimize cycle inventory.

Likewise, firms reduced their batch quantities in accordance with the new demand reality, which required more frequent changeovers. However, surplus personnel were available at virtually no incremental cost. Further, an increasing number of firms implemented analytical safety stock targets to avoid or reduce safety stocks and aligned their processes based on the management of slow moving items.

Streamline service offerings. Finally, successful firms streamlined their service offerings to customers based on their value-add. One well-known trade-off in inventory management relates to the service level that is offered to customers: higher service-level targets require greater safety stock inventory. During the crisis, successful firms reduced their service levels to move from a full-service to a cost-efficient setup. In one case, a supplier to the furniture industry reduced service levels from 98 percent to 90 percent unless products were in heavy competition, provided significant value-add, or customers were willing to pay a premium for higher service level.

Furthermore, firms aligned their Make To Stock/Make To Order (MTS/MTO) mix to eliminate inventories, particularly for SKUs that were sold to a single customer only. However, this approach required careful communication with customers, as they were required to plan and order these now-MTO items further in advance. After the crisis many companies relaxed their strict standards on the service offering while successful firms introduced new processes to carefully evaluate which items to really serve from stock.

Preparing for the Up-Swing

As the Financial Crisis began to ease in 2009, numerous managers were caught by surprise by the sudden economic upturn. For example, the demand plan of one transportation equipment company suggested a slow return to pre-crisis demand levels over the course of six years. Nevertheless, in less than two years, demand bumped back to the previous dizzying heights. Likewise, many firms were still in the right-sizing mode and realized the challenges of moving from full reverse to full steam ahead as production capacities had been reduced and talent had been released.

However, far-sighted firms were prepared for the upturn and managed to gain significant market share by meeting customer demand while competitors struggled. We have identified three practices that enabled firms to successfully meet the increased demand at the end of the crisis: (i) retaining and developing talent; (ii) preparing long-term projects; and (iii) providing upside capacity.

Retain and develop talent. Although the length of the crisis was unclear to most managers, many successful firms realized the utmost importance of retaining and developing talent throughout the recession. Because manufacturing processes in many countries have become more complex in recent decades, the importance of expertise has similarly skyrocketed. Although firms had to lay off workers while adjusting their capacity, talent retention was crucial for the eventual upturn.

Many firms reduced employee work hours to ensure that the given order book provided sufficient cover to retain key personnel. Another successful example is Germany’s chemical and automotive industry, in which many firms leveraged government-supported part-time work to avoid layoffs (1.47 million employees were operating under part-time government support in May 2009 compared to 0.05 million in May 2008). The ability to retain talent enabled the firms to rebound as the economy began to recover.

Prepare long-term initiatives. Many firms realized that the downturn could also be viewed as an opportunity to prepare long-term initiatives as long as no significant investments were involved. In the boom years before the financial crisis, many firms did not have the resources necessary to carefully review their supply chains, as skilled experts were struggling to maintain pace with business expansion. However, the sudden downturn halted further expansions and provided firms with breathing space to focus on long-term initiatives.

For example, one consumer packaged goods manufacturer reevaluated its manufacturing footprint using the newly available project management capacities that were implemented as investments became available at the end of the downturn.

Provide upside capacity. When planning for business in the Financial Crisis, many firms did not consider the need to provide upside capacity. Although suppliers were frequently required to retain some capacity on standby to prepare for sudden demand increases, many firms did not sufficiently prepare for this scenario and were surprised by labor and asset shortages. One example of upside capacity is provided by a chemical company that needed to employ temporary workers during the upturn.

By paying a temporary employment agency a small standby fee for the preferred provision of personnel, the firm was able to select the temporary workers first when the economy began to recover. Accordingly, the firm was able to take on the temporary workers who had previously been working in the firm, thus minimizing the ramp-up time. Other examples include firms that were able to secure capacity early at key suppliers because they sensed the upcoming increase in demand rather quickly.

Being Agile

Many firms suffered seriously or closed their business during the Financial Crisis: They did not reduce capacity as rapidly as demand plummeted; they lost critical suppliers and thus could not fill customer demand; they nearly went bankrupt because of high inventory levels and a lack of cash; they did not have the talent or the capacity to fill soaring demand and therefore lost market share.

Were these outcomes purely the result of misfortune? In some cases, misfortune was perhaps to blame; however, we believe that the Financial Crisis harshly revealed the weak points in many firms’ supply chains. Based on our experience, we highlighted five key areas that many firms did not sufficiently address. These five key areas are not necessarily crisis-related. In fact,

successful companies do not require significant changes because these firms already address these topics. However, firms that do not consistently consider these key areas are much more vulnerable in downturns. What does this finding mean for the next crisis—economic or on an individual firm level?

First, firms must always be carefully scanning for major changes in its specific market conditions or in the overall economic climate. Managers must ensure demand transparency, establish early warning mechanisms using internal and external data, and reconcile with other functions as well as suppliers and customers. To accomplish these goals, managers must establish the relevant processes.

In addition, firms must constantly challenge and test their abilities to adapt to major changes in demand and supply. One valuable tool is an agility assessment of the supply chain to determine whether a firm is truly prepared for an inevitable downturn. Numerous firms have already embedded semi-annual or annual agility assessments into their routine risk management processes. In this context, alternative demand scenarios are outlined, and supply chain adaptations and contingency plans may be developed.

Overall, we believe that firms should continuously improve their agility, which is a means of ensuring success in any economic situation. Fewer stockpiles are accumulated when state-of-the-art inventory management policies are implemented, capacity can be adjusted quickly when contracts with suppliers are designed intelligently, and supplier bankruptcies can be handled easily when alternative sources are constantly identified.

For firms that have not yet become sufficiently adaptable in this regard, now is the proper time to begin working on the measures recommended here—in other words, before the next crisis.

End Notes

1. Peels, R., Udenio, M., Fransoo, J. C., Wolfs, M. & Hendrikx, T. (2009): Responding to the Lehman Wave: Sales Forecasting and Supply Management during the Credit Crisis, as BETA Working Paper Series, nr. 297, December 5th 2009, p. 1-20

2. Dooley, K. J., Yan, T., Mohan, S. & Gopalakrishnan, M. (2010): Inventory Management and the Bullwhip Effect during the 2007-2009 Recession: Evidence from the Manufacturing Sector, Journal of Supply Chain Management, January 2010, Vol. 46 Issue 1, p. 12-18

3. Hoberg, K. Udenio, M., Fransoo, J. C. (2013): How Did You Survive the Crash? An Empirical Analysis of Inventory Management Capabilities in the Financial Crisis. Working Paper.

About the Authors

Kai Hoberg is associate professor of supply chain and operations strategy at the Kühne Logistics University. He can be reached at [email protected]. Knut Alicke is master expert of McKinsey & Company and a member of the global leadership team of the supply chain practice. He can be reached at [email protected].

Download: Deloitte’s 3rd Quarter 2014 Global Economic Outlook